As we enter the final month of what has turned out to be a horrible year for markets, it’s perhaps worth re-examining the perceived root causes of higher inflation and interest rates and how these may change globally and locally next year. Chris Gilmour digs in.

US Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell was quite correct in his basic assumption that inflation caused by the reaction to the Sars-CoV-2 pandemic would only be “transitory”. He correctly forecast that, as consumers started enjoying the lifting of restrictions such as lockdowns, they would go on spending sprees and spend their accumulated savings. But eventually those savings would run out, shortages would disappear and inflation would subside.

So far, so good.

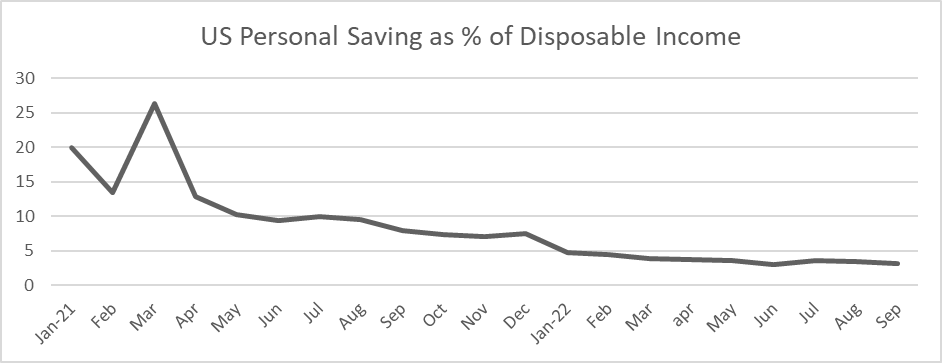

The above graph shows US personal saving as a percentage of disposable income, which reached a recent high of over 25% but which is now at less than 5%. There’s nothing left from this source, so had this been the only source of higher inflation, Powell’s assertion that inflation was only transitory would have been completely correct. But there were many other factors, affecting both the US specifically and the rest of the world via seriously debased currencies.

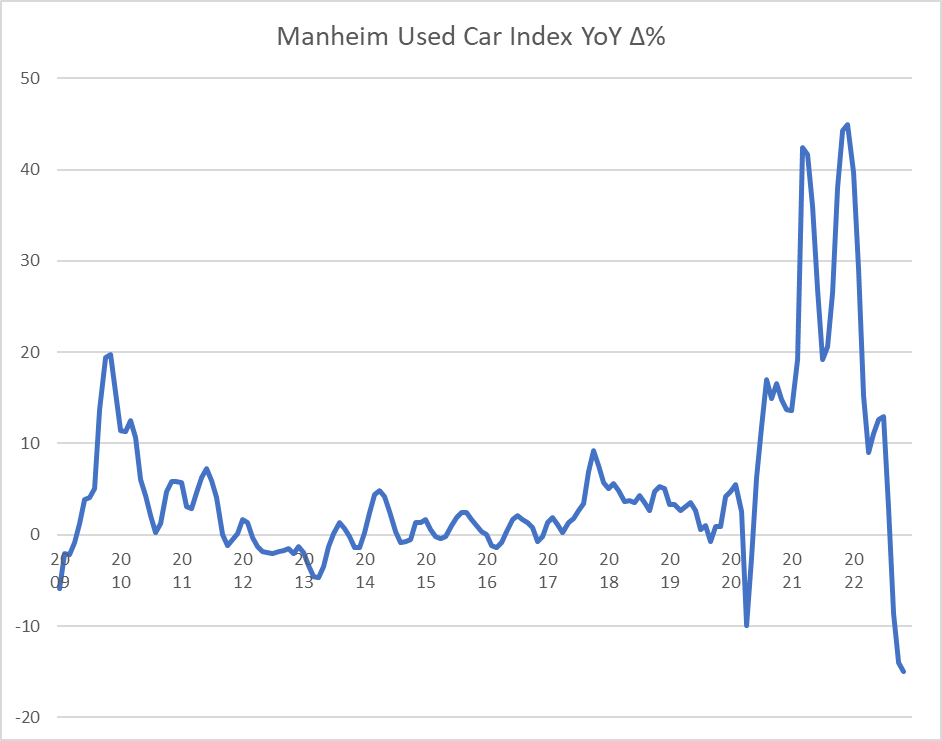

For example, supply chains out of China were badly disrupted as a direct result of the pandemic. Semiconductors stopped being manufactured in Asia almost completely and didn’t restart until well into the recovery stage of the pandemic. This resulted in massive shortages of everything that used silicon chips in their manufacture, including automobiles. A crazy situation arose, whereby second-hand (“pre-owned” in car dealer-speak) vehicles were selling for more then new vehicles, simply because they were available and new vehicles weren’t.

But that phenomenon has now run its course and second-hand cars are now approximately 13% lower in price than they were a year ago, according to the Manheim Used Car Index in the US. So there’s another factor that is no longer contributing to inflation:

The two main input costs that contributed most to inflation around the world – fuel and food – are abating rapidly in US dollar terms. The oil price as proxied by Brent crude is back where it was in January this year, before the start of the war in Ukraine. And food prices, according to the UN Food & Agricultural Organisation (FAO) are similarly in steep decline in US dollar terms.

It’s important to understand the dynamic affecting fuel and food prices in currencies other than the US dollar, however. As the dollar has surged in value, thanks to generally rising US interest rates, most other global currencies have declined in response. Thus commodity prices in these currencies haven’t shown the same declines as those in dollar terms and that situation will prevail for as long as the dollar remains strong.

Another factor contributing to inflation, via the creation of an artificially tight labour market, is the continuation of the Great Resignation. At both ends of the socio-economic spectrum in countries with high degrees of social welfare spending is the phenomenon post-pandemic of people deciding that they’ve had enough of working. At the upper end of the spectrum, people on so-called “final salary” pension schemes (called defined benefit in SA) are retiring early, deciding to vasbyt until their pensions become payable and in the meantime live frugally off savings. At the lower end of the spectrum, people are deciding to stop working altogether and rather just live off state benefits.

The net result is the same: there is a shortage of people to fill vacancies in these countries and that situation could persist for some time. This is a structural problem, rather than a cyclical event.

And in similar vein, the onshoring of manufacturing back to the US and away from China and other parts of far east Asia is also a structural shift. Many countries have decided that it’s more important to be able to rely on continuity of supply than to make lowest price for manufactured products the main criterion.

So for a number of years, expect structurally higher inflation in manufacturing processes than would otherwise have been the case, until these countries reach similar levels of output and productivity as China currently offers.

The good news is that both inflation and interest rates are likely to peak in 2023. Of course, the bad news is that by then the world will be in recession.

Views on how deep that recession may be differ markedly among top economists. Mohamed El-Erian of Allianz remains pretty bearish on the outlook for interest rates, while superbear Jeremy Grantham of GMO is maintaining his stance that a bubble is about to burst. While I respect Grantham’s analytical skills hugely, he is usually wrong on the markets, at least when it comes to timing. And of course arch-bear Nouriel Roubini of NYU Stern is persisting with his doom-laden outlook. In my experience, when all the merchants of doom are predicting pretty much the same thing, chances are it will turn out nothing like that.

Let’s wait and see.