Keith Haring’s career as a commercial artist is absolutely booming at the moment, which would be a big deal for him if he hadn’t died 34 years ago. Even if you don’t recognise his name, you’re sure to recognise his artwork, which has made it onto shirts, mugs, cellphone covers and pretty much every other printable surface in the last three years. This begs the question: why Keith, and why now?

As an artist myself, I’m never one to put down the success of another artist. But I will admit that I range between confusion and mild irritation whenever I spot a child wearing a sweatshirt emblazoned with one of Keith Haring’s ultra-recognisable designs. It’s not that I don’t think Haring deserves the recognition. As an artist who used his unique talents and popularity to bring awareness to the AIDS crisis in the 90s, he absolutely deserves all the praise and attention. I just don’t understand why this is happening more than three decades after his death.

First, let’s talk about the man and his work

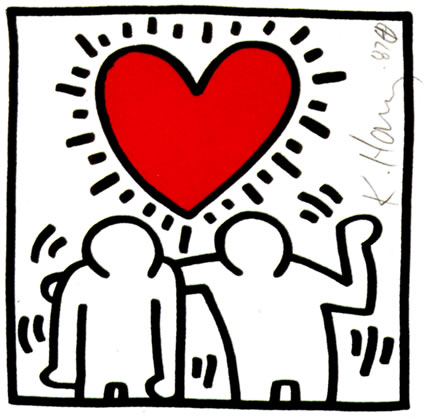

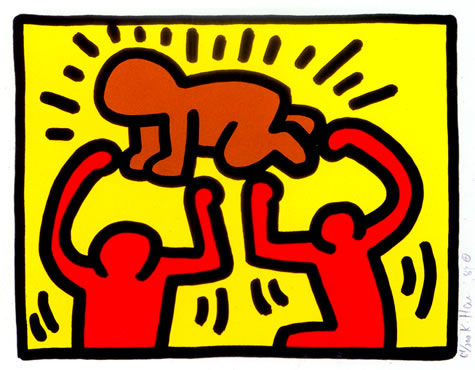

Keith Haring played a pivotal role in the vibrant New York art scene of the 1980s, leaving an indelible mark with his colourful creations and iconic motifs. Beyond the graphic visual allure of his works, Haring’s art served as a powerful response to the pressing social and political issues of his time.

Haring directed his creative energy towards addressing crucial events like the battle against apartheid, the AIDS epidemic, and the issue of drug abuse. As an openly gay artist, he didn’t shy away from representing the struggles faced by the LGBTQ community, championing the cause of gay rights through his art.

Inspired by the raw and expressive nature of graffiti artists, Haring transformed empty poster spaces in New York’s subway stations into canvases for his chalk drawings. His motivation was to break down barriers and make art an accessible experience for everyone. These impromptu works, visible to passersby on a daily basis, allowed Haring to engage with a diverse audience, fostering a connection between art and the public that transcended traditional gallery spaces.

Make no mistake: there is an inherent product-mindedness in Haring’s work. His dedication to the notion of accessible art really paved the way for his designs ending up on t-shirts – in fact, this is an idea that Haring embraced throughout his career. His “Pop Shop” opened its doors in 1986 in the Soho neighbourhood of Manhattan, NYC. The curated selection of products at The Pop Shop went beyond conventional art offerings to include t-shirts and novelty items adorned with Haring’s unmistakable motifs. This innovative approach to merchandising not only made Haring’s art tangible but also turned everyday objects into canvases for his bold and dynamic visual language.

Keith Haring dedicated himself to raising awareness about the AIDS epidemic, a cause that became deeply personal when he received his own diagnosis in 1988. In the wake of his diagnosis, Haring took a decisive step by establishing The Keith Haring Foundation just a year later. This foundation became a beacon of support, providing crucial funding and resources for AIDS research, charities, and educational initiatives. Keith Haring succumbed to AIDS-related complications on February 16, 1990, at the age of 31. Since then, his body of work has been managed by the Keith Haring Foundation.

Haring: the new Kahlo

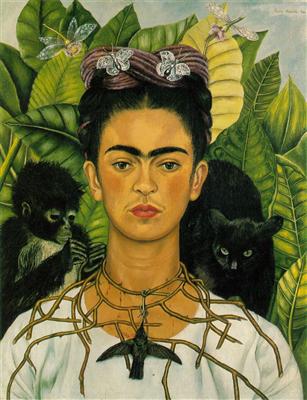

The Haring phenomenon isn’t the first example of a prominent (dead) artist becoming hyper-commercialised to this scale. Just a few years ago we were all still firmly in the grip of Fridamania, with images of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo slapped on everything from throw pillows to coasters, like this one from The Cushion Mall:

The height of the global Frida obsession is estimated to have been around 2017 – 63 years after her death – but the commercial remnants of that time can still be found in the corners of gift shops across the globe. From vials of nail polish and lip glosses to Kahlo-themed cafés, restaurants, and street murals that dot urban landscapes, the prevalence of her image reached new heights. Even seemingly mundane items like bars of soap and posters became canvases for celebrating Kahlo’s distinctive features: her hair braided into a regal crown adorned with colourful flowers, her unapologetic monobrow, and the piercing intensity of her defiant gaze.

Like Haring, Kahlo used her work to speak to particular issues that were close to her heart, such as feminism and her Mexican heritage. Adriana Zavala, an esteemed scholar specialising in Latin American art at Tufts University and the curator behind Frida Kahlo’s 2015 exhibition at the New York Botanical Garden, offers a thought-provoking perspective on the pervasive presence of Kahlo paraphernalia. According to Zavala, the widespread availability and consumption of Kahlo-themed merchandise has, over the course of three decades, led to a dilution in the nuanced understanding of the Mexican artist’s profound contribution to art history.

After all, how many of the people decorating their homes with Frida fridge magnets and coffee mugs are aware of her artistic journey and the messages that she expounded through her work? In the same vein, are the parents who are dressing their toddlers in Keith Haring onesies aware of how much work he did on major social issues?

So, who’s getting paid for this?

Every time Mickey Mouse has been printed on a sweatshirt, Disney got a cut of the profits of its sale through licensing fees. Interestingly, the original image of Mickey Mouse has finally entered the public domain in 2024! Leaving that aside, how does licensing work when the original creator of an image is deceased?

In the case of Keith Haring, licensing is handled by his foundation. Under US law, Haring’s copyright to his own work lasts 70 years post-mortem. His foundation will continue to handle all licensing (and collect all fees) for the next 36 years. For Frida Kahlo, things are a bit more complicated, as her copyright is held under Mexican law, which protects the copyright of artists who died before 1956 (like Kahlo) for only 25 years post-mortem. Kahlo also died intestate (without a will) and had no children, which meant that her intellectual property was automatically handed over to the closest living heir, which happened to be her niece, Isolda Pinedo Kahlo.

If I had to detail the intricacies of the legal battles that ensued over Kahlo’s intellectual property after those 25 years elapsed, I’d have to write another 100 pages. The long and the short is that a corporation was started to manage Kahlo’s works, and there has been a long and arduous tussle between said corporation and her family for years. If you want to really get into it, you can read on here.

Of course, we’re assuming that every corner store that sells a Frida Kahlo or Keith Haring t-shirt is, in fact, doing the right thing and paying licensing fees where they are due. Since the internet exists and images can be accessed for free by anyone who knows how to work a computer mouse, the far more likely truth is that many small-time manufacturers are flying under the radar and getting their prints for free.

As for my original question…

I wish I could tell you that my extensive research on this topic has led me to some interesting and insightful reason behind the current Haringmania. But alas, my question remains largely unanswered. I don’t know why the global hive mind has settled on Haring in particular as the artist of the season. Is the team at his Foundation just really good at securing licensing deals? That may be so – but then again, why so many different brands, and why now, an arbitrary 34 years after his death?

I turn to you and your theories, gentle reader. Have you noticed a surge in Haring imagery around you recently? Why do you think that may be? Let me hear your best guesses in the comments below.

About the author:

Dominique Olivier is a fine arts graduate who recently learnt what HEPS means. Although she’s really enjoying learning about the markets, she still doesn’t regret studying art instead.

She brings her love of storytelling and trivia to Ghost Mail, with The Finance Ghost adding a sprinkling of investment knowledge to her work.

Dominique is a freelance writer at Wordy Girl Writes and can be reached on LinkedIn here.

Great article!

I suspect that David Stark and his Artestar agency are behind this. Stark used to work for Haring up until the artist’s death and managed his estate afterwards for many years. He founded Artestar in 2003 to do artist / brand collaborations, with Haring at the forefront.

In 2018 they entered China with a Haring / Coach matchup, found fertile ground in the Gen Z demographic and WHAAM! 🙂 Looking at the Artestar lineup, we can look forward to Basquiat, Mapplethorpe, etc, etc.

Why Haring? Besides the connection with Stark, I think his art lends itself well to commercialisation. It’s simple, colourful, instantly recognisable and not too edgy. I wonder who will go big next…

That’s a really interesting take, thanks Ludwig!

I agree with you that Haring’s work was made to go commercial – I guess I was just hoping to stumble on some pivotal event (like an important retrospective) or significant anniversary that acted as the catalyst for his sudden reappearance. But I tend to think that you’re right here, and that it all comes down to business connections at the end of the day.

Basquiat could be an interesting “next big thing”. I shudder to think what a Mapplethorpe moment would look like! They’ll have to but a PG rating on the homeware section at H&M if that happens, haha!

I agree with you on Mapplethorpe 🙂 I even tried to imagine Blake, Goya and Bosch versions of brands, but for some reason the older artists don’t cut it. It looks like you need IP to make it work.

You could even argue that Haring himself is behind this, given his philosophy of democratising art, taking it out of the museums and galleries and spreading it far and wide. This ethos inspired Stark to go big.

The interesting thing is that all the commercial hype now feeds back to museums, with “blockbuster museum exhibitions launching for Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kenny Scharf, Tom Wesselmann and Mickalene Thomas” over the next two years, according to Stark. So the retrospectives are following the trends instead of setting it at the moment.

On the timing: I guess the time is just ripe for such collaborations.

First we had music. Partnerships and quirky mashups have always been big in music, but these days “A feat. B” is over the top. I just scanned Apple Music’s Today’s Hits playlist and 31 of 104 songs credit multiple big-name artists. Then we had all the “A x B” fashion collabs. Now it’s art’s turn, it seems.

It’s a powerful mathematical principle: rather than sourcing 45 unique ideas, just take 10 and combine then in pairs. The power of multiplication 🙂 If you are still not happy, combine them in triplets. There are diminishing returns, though!

Thanks for another great article Dominique.

There are other examples of works of art being used for commercial purposes. Two of the most famous are Van Gogh’s Starry night and Munch’s The Scream, both painted about 130 years ago. Starry night has inspired designs on mugs, shoes, jewellery and pretty much everything else. And of course it inspired Don Maclean to write his hit song. The Scream is often used as masks for bank robbers in movies, for getting out political messages about the awfulness of your opponents and Macaulay Culkin popularised it in the Home Alone series.

The questions are, like your questions: why these images rather than others? What made them ideal for this purpose? What was the trigger? Who/what started the movement? Is it just a coincidence that both Van Gogh and Munch had mental health problems?

I don’t have the answers, sadly, but would be interested in your views.

You’re not wrong Tim – there certainly has been a history of artworks being commercialised after their creators have passed on. I guess what stood out to me the most about the Haring and Kahlo phenomena is how in both cases it is one artist seemingly coming out of nowhere, dominating shopfronts for a few seasons and then quietly disappearing into obscurity again, whereas the Van Gogh and Munch artworks that you mentioned pop up more sporadically over a greater length of time.

There have been some really great theories about the why and how in this comment section already – make sure you read Ludwig’s first comment in the thread above for a really great clue about Haring’s work!

I think that Haring’s style representing an awareness of sexuality and sometimes being at odds with the world as to a person’s sexual identity feels a gap in the art world of today. Gender definitions and acceptance throughout society including the church is the buzz topic of this century . There are sixteen terms/titles at present which define which side of the gender one tends to favour. Maybe just wearing or using an item with his distinct style minimises a definition !

You might be on to something Colleen! Haring certainly does fit in with the current discussions around gender and sexuality.