Chris Gilmour writes weekly for Ghost Mail, sharing his international perspectives and on-the-ground insights into what the global investment community is focusing on.

There was a time, not so long ago, when nominal interest rates in a number of European countries, such as Switzerland, were negative. Banks were physically charging their customers to accept bank deposits, rather than paying them interest. Inflation was virtually non-existent in these countries, so the concept of real interest rates wasn’t especially important. That has all changed in recent months as inflation and interest rates have taken off.

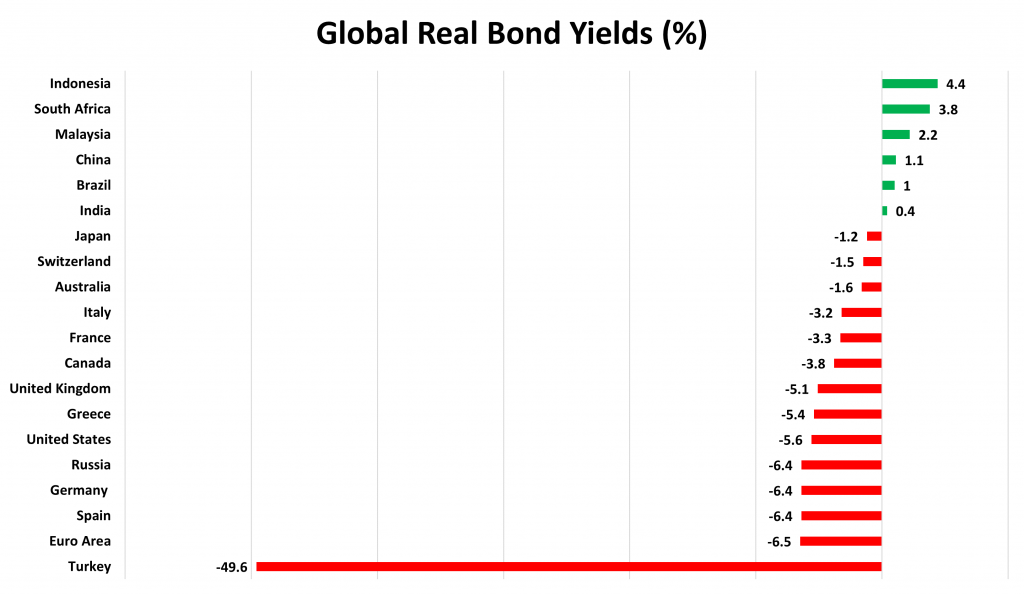

Virtually all countries, including Switzerland, now have at least marginally positive nominal interest rates and only Japan has zero interest rates. But because inflation has been rising much faster than interest rates have been rising, much of the world is now experiencing negative real interest rates. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Turkey, where inflation is now averaging just under 70%, while their ten-year bond yield is reading at just above 20%. In other words, a negative 50% real interest rate!

At the other end of the spectrum, Indonesia and South Africa are currently offering 4.4% and 3.8% real yields respectively. And in between, there is a huge range, with only ten out of 40 countries offering real yields, the rest having negative real yields.

Britain is a particularly interesting case. Until recently, its interest rate was at a 300-year low. Bank rate, as the Bank of England refers to their version of the repo rate, has moved up by 90 basis points from 1.1% in October to the current level of 2%. That’s a huge rise in percentage terms (82%) but the rise in inflation during the same period is far more profound. The latest inflation print from the Office for National Statistic (ONS) showed that British inflation hit 9% in April, a more than doubling from the 4.2% rate of six months previously, in October 2021. The real interest rate at which people can borrow from the UK banks is thus 2% minus 9% =-7%. Historically, this is extreme. As British inflation prints even higher as the year progresses, it will start entering uncharted territory.

This is going to result in a major headache for policy makers, not just in the UK and the US but in all countries where interest rates are now highly negative. At a time when governments would be happy for consumers to batten down the hatches and stop spending as part of an overall effort to curb inflation, human nature dictates that it makes sense to borrow as much as possible at negative real interest rates. The only way to curb that type of behaviour is to increase interest rates significantly but in so doing, the risk of stagflation in an economy becomes very real indeed.

Thus the likelihood is that central banks will stick to the pattern of only increasing interest rates by relatively marginal amounts, for fear of stalling the global economy. Consumers, on the other hand, will see this as an opportunity to buy assets with incredibly cheap money, raising the possibility of another bubble in consumer credit. Corporates, too, will see this as manna from heaven – the ability to execute acquisitions using debt, the cost of which is getting wiped out very quickly. Private equity firms will be able to borrow up to the hilt and beyond, buy out cash-cow companies with stable cash flows and use those earnings to pay back the debt. That has already happened in the UK with the private equity buyouts of both Asda and Morrison’s. That was before the great inflation, so just imagine how attractive these situations must look to private equity companies now. Retailers such as M&S and Sainsbury’s must be in the firing line.

And if interest rate rises are going to continue to lag inflation rate rises, then putting one’s money in interest-bearing deposits doesn’t really make an awful lot of sense; the capital value will be quickly eroded by inflation. Thus, even though a global bear market in equities appears to be developing, it may be short-lived, if only because the alternative of “investing” in interest-bearing securities makes no sense after adjusting for inflation.

Of course, it’s very different in South Africa, where interest rates are still marginally positive at a borrowing level. The prime lending rate following SARB governor Lesetja Kganyago’s speech on Thursday 19 May is now 8.25%, with inflation currently at 5.9%. So, no chance of a debt bubble in South Africa yet, as long as interest rates keep on rising. The inherent danger in such a policy is that any residual economic growth that might have been expected this year and next is now in danger of being snuffed out. But the governor had little room to manoeuvre, as he knows full well that in a rising interest rate environment globally, South Africa needs to be able to continue attracting foreign capital due to its high real bond yields.

The following chart shows an attenuated version of global real bond yields, highlighting South Africa’s position near the top of the real bond yield league (date source: The Economist):