Chris Gilmour writes weekly for Ghost Mail, sharing his international perspectives and on-the-ground insights into what the global investment community is focusing on.

South Africa’s infrastructure used to be highly regarded globally. Its road system in particular was world-class, as was its electrical utility company Eskom. Its water reticulation systems were easily the best in Africa. The rail system, though based on the quaint so-called “Cape gauge” track width of three foot six inches, nevertheless worked well.

But that’s all changed now.

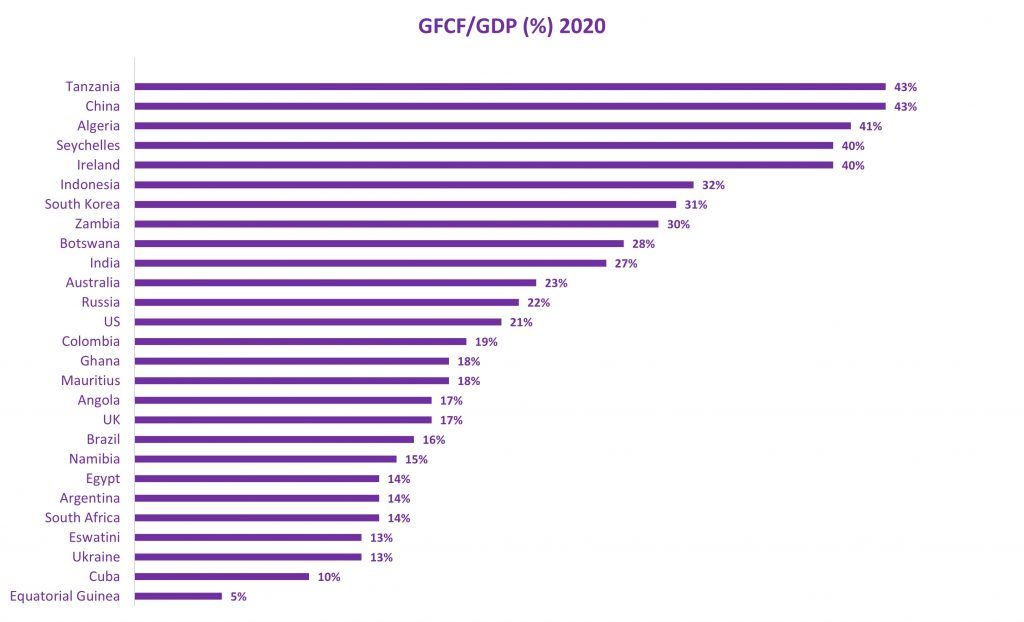

As a percentage of GDP, gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) reached a peak of 32% in 1976 and with the exception of the blip in the noughties associated with the FIFA World Cup stadium construction and the Gautrain, that percentage has been in secular decline ever since. At 14% in 2020, it was the lowest it had been since 1960. The average for all countries covered by the World Bank is 26%, so South Africa is a little over half the global average. In an IMF report on infrastructure earlier this year, it was reported that SA’s GFCF to GDP had reached an all-time low of 12.2% in 2021.

The net results can be seen in the badly potholed road system (apart from the arterial trunk roads, which still seem to be in reasonable condition), the fact that Eskom has now been indulging in rotational power cuts (loadshedding in Eskom-speak) for 15 years and the fact that many of the waterways are heavily polluted with raw sewage. Additionally, the rail tracks are literally being stolen from under our noses on an industrial scale.

It should come as no surprise that South Africa ranks extremely poorly in the World Bank’s ranking table of GFCF to GDP. Only Equatorial Guinea, a basket-case, Cuba (a failed state where little or no material infrastructure spend has occurred since the late 1950s), Ukraine and Eswatini have lower GFCF to GDP ratios.

But there may be light at the end of the tunnel, at least in certain areas of infrastructure development. The good news is that President Ramaphosa unveiled plans to materially boost SA’s infrastructure spend in late 2020. The bad news, according to a report released by Standard Bank on May 25 this year, is that a quarter of South Africa’s R340 billion worth of strategic infrastructure projects have been delayed or put on hold.

A recent article by Antoinette Oosthuizen from Futuregrowth Asset Management dimensions the impending water crisis in South Africa and offers practical solutions to that crisis:

“The challenges that confront the country are varied. Old/aging, poor quality and poorly maintained infrastructure is contributing to high levels of water wastage and the pollution of rivers and groundwater with sewage. Climate change is driving the country towards a warmer and drier future, with longer, more extreme droughts and more intense floods predicted.”

This is especially apparent given the tragedy of the recent widespread flooding in KZN, the worst natural disaster in South African history.

According to Oosthuizen, capital expenditure on the second phase of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP-2) is expected to increase substantially from 2022/23, as construction ramps up. The combined debt of the augmentation schemes in the Vaal River System must be repaid within 20 years after completion of LHWP-2, with estimated water delivery in 2027.

Eskom appears to be an altogether more intractable problem, with a massive debt burden of just less than R400 billion compounding a host of operational issues. In addition, sabotage at the Tutuka and other power stations is causing a far greater incidence of rotational power cuts.

But even here, there are signs that things may be improving, at least from a broad perspective. Industry and the mines were recently given the authority to generate up to 100 megawatts of power internally. An increasing number of people who can afford it are migrating off the Eskom electricity grid via installation of rooftop solar panels and battery arrays. Even if Eskom is unable to put in new capacity, a far higher commitment to renewable energy development should help boost infrastructure spend.

According to the Standard Bank report, the rollout of one project – a plan worth billions of dollars to build 2,000 megawatts of new power-generation as quickly as possible – has been held up by court cases and Eskom. This couldn’t have happened at a worse time, as South Africa heads for a record year of disruptive rotational power cuts as Eskom is incapable of meeting even the current diminished demand for electricity.

The national road network is a SANRAL competency which it appears to be executing reasonably well, with a few exceptions. A new funding model will need to be found for the Gauteng Highway Improvement Project, as motorists have made it very clear that they are not prepared to pay via electronic gantries on a user-pays basis. The worst examples of potholes and other road degradation are to be found in the urban areas, where municipalities have been failing dismally to keep roads in good shape. As long as municipalities are regarded by certain political parties as an easy way to make money, this poor road situation is likely to persist.

Having said that, Raubex recently posted strong results and made mention of the SA government’s higher level of infrastructure spend.

This just leaves the national rail network. During the depths of the pandemic, a great deal of metal in the stations and on overhead power cables was stolen. It is only very gradually being replaced. Railtrack has been stolen and in certain areas, shacks have been built on the tracks. It is difficult to think of anywhere in Africa where a similar situation persists.

And for over a decade now, the Chinese have been making plans to establish a high-speed rail link between Johannesburg and Durban that would carry both passengers and freight. This would be constructed on international gauge track – the same width of track as Gautrain – but as yet is only really seen as a possibility in the minds of politicians.

This is a pity, as this is the stuff that dreams are made of. If a high-speed rail link could be established between Johannesburg and Durban that could cut the journey time from the current approximately 14 hours to nearer 4 hours, it could compete head-on with the airlines, when all-in logistics are taken into consideration. And for a developing economy such as South Africa, that is precisely what is required. Also, putting more freight back onto the railways and taking it off the roads would result in far less damage being done to the road network.

Considering how far South Africa has fallen on the global infrastructure ranking, even if only a few new big projects get commissioned in the next few years, the effect could be profound, albeit from a low base. It’s quite conceivable that SA’s GFCF/GDP could double in five years if everything manages to align. Here’s hoping.