Nestlé has been the largest publicly-held food company in the world, measured by revenue and other metrics, since 2014. It is also the company on the receiving end of the longest continuous boycott in history. What do these two facts tell us about supersized businesses and the consequences of behaving badly?

I don’t have many vices, but one of the few that I’ve had since childhood is a hot cup of Milo on a chilly day. In my opinion, there is no other malted drink that compares in taste (sorry, team Ovaltine). This is a tough thing for me to deal with, because while I love that signature Milo flavour, I’m deeply conflicted about the business practices of its parent company, Nestlé.

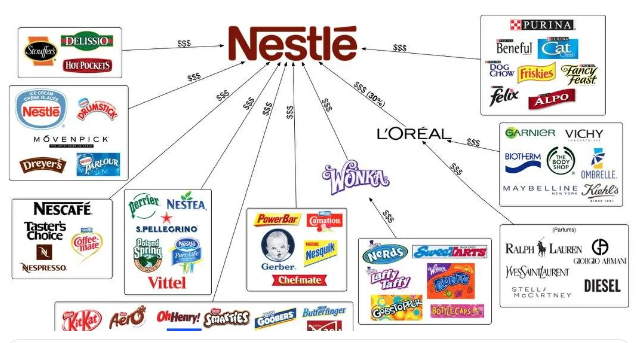

You might attempt to solve this moral conundrum for me by suggesting that if I feel so strongly about Nestlé’s practices, then I should avoid buying their products. A reasonable idea, but much harder to execute than you might imagine, considering the vast amount of brands and products that Nestlé owns. Besides, when you look at Nestlé’s market share, you really have to ask yourself: is a boycott even remotely worth it?

How Nestlé got on the naughty list

In 1974, a document was published that would change public perception of the Nestlé brand forever. Titled “The Baby Killer”, this investigation by journalist Mike Muller was an unflinching exposé of the dodgy tactics used to market baby formula in third-world countries, particularly Africa. While the piece was directed at formula makers in general, there was no escaping the implication that Nestlé was one of the biggest culprits, with the company’s “Mother’s book” (a booklet handed out to new mothers in maternity wards, for free) referenced multiple times in the report.

From a marketing perspective, these tactics seem clever and effective. Scores of Nestlé brand representatives, dressed in nurse’s uniforms, were sent into maternity wards across Africa, Chile, India, Jordan and Jamaica, armed with free samples of baby formula. In the wards, they would speak to new mothers about the benefits of infant formula, a modern Western innovation that, according to them, far surpassed ordinary breastmilk in terms of nutritional value.

Impressed, many of these new mothers would test the formula sample on their babies, unaware that the milk in their own breasts would dry up by the time the sample tin was finished. Now imagine the tin is empty, the baby has become accustomed to the taste of formula, and the mother has no breastmilk left to offer as a substitute. There is no choice but to keep purchasing the product, despite its high cost (in Nigeria at the time, the cost of formula-feeding a 3 month old infant was approximately 30% of the minimum urban wage). Desperate mothers, trying to “stretch” the amount of formula in the tin, would stray from package guidelines, over-diluting their formula by adding as much as three times the amount of water required. Despite the fact that they were feeding their babies regularly, they were filling their tummies with mostly water, which cannot provide the calories or protein that a growing infant needs to thrive.

Water, of course, is the other massively overlooked problem in the formula recipe. Anyone who has ever had the experience of bottle-feeding a baby will know the tedious sterilisation routine required at almost every step of the process. In a West African hospital, a new mother has access to boiled water whenever she asks for it. Back home in her village, access to water is limited, as is the ability to boil it every time a bottle needs to be made. In some instances, baby formula is mixed with water collected from the nearest river. In young infants who were not yet of age to receive vaccinations against these diseases, this led to an uptick in cases of diphtheria, dysentery and typhoid, many of which are fatal.

Over-diluted formula, unsanitised bottles and unclean water led to the sickness, underdevelopment and eventual malnutrition of a huge amount of babies in third-world countries between the 1970s and 80s. Where third-world mothers had a perfectly nutritious, convenient and free resource available to them and their babies in the form of breastmilk, they were deliberately convinced of its inferiority in order to get them to make the commitment to formula.

Bring on the boycott

You can imagine the absolute uproar that this exposé was met with in the first-world. Boycotts were launched against Nestlé products in numerous countries, and an international marketing code (the ‘WHO Code’) was developed to prevent the comparison of manufactured baby milk with breastmilk. In response to the clamour (and perhaps in an effort to save some face), Nestlé introduced its own policy based on the code during the 1980s.

Unsatisfied that these steps were enough to curb irresponsible marketing, a UK-based group called Baby Milk Action has been running a boycott of Nestlé products since 1988. To date, this is the longest-running continuous boycott that the world has ever seen. Baby Milk Action has grown from a movement to a serious organisation with a network of over 348 citizen groups in more than 108 countries, all of whom encourage their members to boycott Nestlé’s products.

Idealistically, you would think that this is a real thorn in the side of Nestlé. Not only is that not the case (certainly not as far as the company’s market share is concerned), but it hasn’t even done that much to get Nestlé to change its ways.

In 2019, Nestlé’s own report found 107 instances of non-compliance with the baby milk marketing policy that it wrote for itself. A Changing Markets Foundation report from the same year found that Nestlé was still comparing its own products with human milk.

Too big to be held responsible?

I wish I could tell you that the formula debacle is the only questionable course of action that Nestlé has been involved in, but that’s not the case. From their memorable attempt to argue that water is not a human right (a useful win for a company that sells bottled water) to their decades-long entanglement with child slave labour in the plantations that supply their cacao, this company has proven time and time again where humans fall in their hierarchy of priorities.

While consumers like you and I aim to wield significant influence by voting with our spending, the uncomfortable truth is that the outcome of a boycott often hinges on the brand’s resilience, rather than consumer sentiment. Brands that are easily substituted are more susceptible to boycott pressure. Conversely, companies with substantial market dominance present a formidable challenge for the consumer-led movements that aim to impact their profits.

That’s because the fundamental obstacle for most boycotts lies in the intrinsic value companies imbue in their products, cultivating a perception of indispensability in consumers’ daily lives. In the case of Nestlé, an added complication is that the company is so big and owns so many brands that it takes a lot of legwork for even the most conscientious consumers to identify and avoid all of them.

So if we accept that individual purchasing decisions may not make that big of a difference to Nestlé’s bottom line, does that mean that the company is simply beyond reproach? I don’t think so. In the case of Nestlé, we’ve already seen how the original boycott in the 1980s led to the institution of the international marketing code.

Perhaps what’s needed is less consumer action and more rules that keep these mega-corporates in line.

About the author:

Dominique Olivier is a fine arts graduate who recently learnt what HEPS means. Although she’s really enjoying learning about the markets, she still doesn’t regret studying art instead.

She brings her love of storytelling and trivia to Ghost Mail, with The Finance Ghost adding a sprinkling of investment knowledge to her work.

Dominique is a freelance writer at Wordy Girl Writes and can be reached on LinkedIn here.

Great article!