Get the latest recap of JSE news in the Ghost Wrap podcast, brought to you by Mazars:

ADvTECH achieved a 45% increase in the dividend (JSE: ADH)

The year ended December 2023 was cause for celebration

Revenue for the year ended December 2023 increased by 13% to R7.86 billion. The story gets even better from there for ADvTECH, with operating profit up 18% to R1.577 billion. HEPS jumped by 19% to 174.2 cents per share, putting the icing on the cake in terms of a strong revenue increase translating into a great HEPS outcome.

The dividend per share is 45% higher for the year, coming in at 87 cents per share. That’s a modest payout ratio, indicating that the group is retaining significant funds for growth.

The Schools Rest of Africa division was the star in terms of growth, with operating profit up 43% to R114 million. Schools South Africa achieved 18% operating profit growth to R570 million. The Tertiary business was up 16% to R787 million and even Resourcing weighed in, with operating profit growth of 20% to R106 million.

Overall, that’s a really strong outcome.

Ascendis makes changes to the independent board and circular (JSE: ASC)

This follows complaints received by the TRP and associated compliance notices

Ascendis has received more than its fair share of attention on social media in the past few months, with the offer to shareholders from the consortium led by Carl Neethling raising all kinds of interesting questions. There’s also been plenty of noise online, which has led to legal action by an Ascendis director against one of the protagonists. It’s been wild out there and I don’t think the story is anywhere near being over!

Without wading into the hornet’s nest of all the fighting online, the important point is that the TRP has investigated the matter and issued compliance notices where appropriate. This has led to a few changes from Ascendis, such as the disclosure around concert parties and who is included in that definition.

Another important change is that Amaresh Chetty has moved off the independent board on a “voluntary basis and in agreement with the TRP”. This is based on a potential conflict of interest.

A supplementary circular has thus been issued and the rescheduled general meeting is in the diaries for Tuesday, 23 April. If you would like to read the entire thing, you’ll find it here.

CA Sales acquires 49% of Roots Sales (JSE: CAA)

The bolt-on acquisition strategy continues

CA&S, or CA Sales Holdings as its full name, has been one of the best recent success stories on the JSE. The share price is up 61% over the past year, which is massive outperformance vs. the rest of the market.

This has been thanks to a solid and dependable strategy with no fireworks or weirdness. Investors love simplicity. They absolutely adore simplicity that leads to profits.

A bolt-on acquisition strategy is the simplest way to grow inorganically. If you can imagine a piece of Lego in your hands, a bolt-on strategy is about taking some blocks and adding them to what you already have. This is totally different to a high risk acquisition strategy that looks for entirely new opportunities, or a new Lego set to build instead of improving the existing one.

CA Sales has acquired 49% of Roots Sales, a business with a ten-year track record in helping consumer brands reach the market in South Africa. Roots services over 8,000 outlets across Southern Africa. This is a perfect fit with the rest of CA Sales’ business and makes a lot of sense. It’s also good news that CA Sales has the option to increase its shareholding in Roots (thereby taking control), exercisable at a point in future.

Appreciation for the Payments division at Capital Appreciation (JSE: CTA)

This side of the business has carried the team in the latest period

Capital Appreciation released a pre-close update for the year ending 31 March 2024. It tells a tale of two divisions, with the Payments side doing well and the Software side struggling in a period of weak demand. Overall, financial performance improved in the second half of the financial year.

In Payments, terminal sales recovered in the second half of the year and the leased terminal estate doubled from the prior year. This bodes well for revenue and profits in years to come. Annuity revenue is now 56% of total revenue in this division, up from 50% a year ago. To assist further, expenses were tightly controlled and actually came down year-on-year, doing excellent things for improvement in margins.

The Software division is singing a different tune, with delayed contracts that impacted profitability after the business was staffed up. It’s incredibly hard to manage a business like this, as the staff need to be there to service the clients but it’s also quite easy for clients to delay projects. Although revenue growth was achieved for the year, the narrative in the announcement is one of challenges in costs. Notably, the recently acquired Dariel Group has been integrated into this division as well.

At GovChat, the company and other GovChat shareholders will share the costs of litigation against Meta, with GovChat given the right to intervene as a direct party in the Competition Commission’s prosecution of Meta. Further funding of GovChat has been limited and losses will be materially lower for this year.

Importantly, the group still has no debt on the balance sheet (despite the Dariel acquisition).

It’s hard to know where to look at Clientele (JSE: CLI)

The interim results look poor, but have been impacted heavily by IFRS 17

Clientele has released results for the six months to December 2023. HEPS fell by 35%, which doesn’t make for a happy starting point. This is based on restated comparatives for 2022 that take IFRS 17 into account.

The annualised return on average shareholders’ interest has dropped to 9%. That’s also not a good story. The introduction of IFRS 17 led to a significant increase in net asset value and a drop in current period profits. The combination is obviously a disaster for return on capital ratios.

It’s quite difficult to know how to interpret the results. Insurance income is significantly affected by yield curves over the period and how they change shape, which can lead to some volatile outcomes in a time of macroeconomic flux.

Group Embedded Value is calculated on the old IFRS 4 basis and increased from R5.9 billion at June 2023 to R6.0 billion at 31 December 2023 despite the payment of a R420.7 million annual dividend. Recurring EV earnings fell 1% vs. the comparative period.

Without a doubt, these earnings were impacted by a large number of factors that aren’t reflective of the core business. It looks as though earnings were under pressure, but the core business probably isn’t 35% worse than the prior year (as HEPS would suggest). The share price had a horrible day regardless, down 12.7%.

Fairvest affirms distribution guidance for the year for the B shares (JSE: FTA | JSE: FTB)

The balance sheet looks good as well

Property fund Fairvest released a pre-close update dealing with the six months to March 2024. The fund is split across retail (69.4%), office (18.8%) and industrial (11.8%) properties, with those splits based on revenue.

Between September 2023 and the end of February 2024, group vacancy moved higher from 4.5% to 5.3%. That’s not great obviously, but it is good news that positive rental reversions of 2.5% were achieved overall. The loan-to-value ratio is expected to be below 34% for the interim period. Perhaps most importantly, the guidance for the full year B share distribution of between 41.5 cents and 42.5 cents has been reaffirmed.

Interestingly, the presentation includes an entire slide dedicated to the Pick n Pay and Boxer exposure. Pick n Pay contributed 1.8% of group revenue and Boxer was 3.9%. Pick n Pay Liquor and Clothing came in at 0.3%. Overall, Fairvest sees this as a low risk to the business.

I must highlight that the office portfolio seems to have suffered the worst of the vacancy trend, up from 9.7% at September 2023 to 12.8% at the end of February 2024. Both the industrial and retail portfolios also saw a deterioration, but to a far lesser extent.

Gemfields concludes another emerald auction (JSE: GML)

These metrics don’t look so great, but the company has tried to explain why

In the comments related to this emerald auction, the Gemfields executive noted that “the commercial-quality emerald market remains in good shape and prices are broadly in line with the September 2023 commercial-quality auction.” Now, that may well be true, but the metrics for the auction tell a different story. The devil seems to be in the detail of the lower-quality emeralds included in this auction, which would normally be sold via a direct sales channel. There were also unsold lots that weren’t typical auction grades. This has skewed the overall auction result.

Of the last five auctions, this auction achieved the worst result in terms of percentage of lots sold by weight. With sales of $17.1 million, it also achieved the lowest total sales result. The price of $4.45 per carat was way off the other auctions, with the lowest of the other auctions at $7.13 per carat.

The market is a tad nervous of Gemfields after the last results and these metrics wouldn’t have helped, despite the company’s efforts to explain them. The market will watch the results of the next few auctions closely.

Separately, the company released its annual report and announced a dividend of USD 0.857 cents per ordinary share. This is miles off the USD 4.125 cents in 2022.

Merafe announces the second quarter ferrochrome price (JSE: MRF)

This is obviously a very important input into expected profitability

For Merafe, the ferrochrome price is the lifeblood of the business. Each quarter, the company announces the benchmark price for the upcoming quarter. This is just how the ferrochrome market works (vs. e.g. a spot gold price).

For the second quarter of 2024, the European benchmark price has been settled at 152 US cents per pound, which is a 5.6% increase vs. the first quarter.

The announcement doesn’t give the year-on-year move, so I went and dug out the equivalent SENS announcement from 2023. For the comparable second quarter, the price was 172 US cents per pound. Although the rand plays a role here, the USD-based price is 11.6% down year-on-year.

MC Mining starts using stronger wording (JSE: MCZ)

Goldway’s efforts to cast doubt on the independent expert valuation have struck a nerve

At one point, I thought we had heard the last of this fight between Goldway as the bidding party and the independent board of MC Mining as the target. Alas, there’s more.

MC Mining has turned up the overall tone of its announcements, particularly in response to Goldway refuting the approach taken by the independent expert in the valuation. The announcement goes into great detail, defending the approach taken and reminding shareholders that the independent board’s recommendation is to not accept the offer.

Either way, shareholders have the opportunity to accept the cash from Goldway (and therefore ignore the independent expert and the board) or trust what the board is saying here. If Goldway doesn’t get enough acceptances though, the entire offer collapses anyway and even those shareholders who were willing to exit at this price won’t be able to do so.

MTN maintains the final dividend despite HEPS collapsing (JSE: MTN)

The payout ratio is now more than 100%

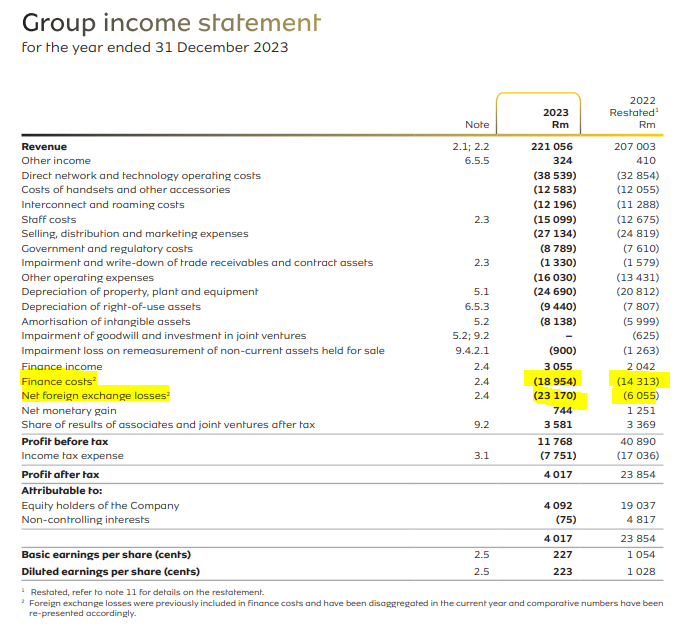

MTN has released its financial statements for the year ended December 2023, giving full details on a year that saw HEPS drop to 315 cents per share (down 72.3%) with the dividend maintained at 330 cents per share. That’s a very unusual outcome, explained by non-operational impacts being responsible for 888 cents per share of the pain in HEPS.

Although there are pockets of strong growth (like data traffic and fintech transaction volumes), group EBITDA was only 9.8% higher year-on-year on a constant currency basis. As reported, it was down 0.5%. On a constant currency basis, EBITDA margin fell by 120 basis points to 41.5%.

To help you understand where everything went wrong, I’ve highlighted the finance costs and especially the net foreign exchange losses in this income statement. Just look at how much higher they are and what that did to group profit:

Those foreign exchange losses relate to MTN Nigeria and they are causing a great deal of pain for shareholders. Although the dividend is unaffected at this point, the pressure can’t continue into perpetuity.

Sasfin releases the circular for the disposals to African Bank (JSE: SFN)

This deal was first announced in October 2023

This circular has been a long time coming. Sasfin is looking to dispose of the Capital Equipment Finance (CEF) and Commercial Property Finance (CPF) businesses to African Bank. This is a Category 1 deal for Sasfin, hence a circular is needed.

This has now been released and is available here for those interested in all the details.

The total deal value is around R3.23 billion. This is based on the loan book values for the two businesses, plus goodwill of R100 million for CEF and an “agterskot” of at least R15.3 million for the CPF business. Sasfin has gotten a decent price here and African Bank is willing to pay it based on the strategic benefits of scale that these acquisitions bring to that group.

Wesizwe Platinum is still loss-making (JSE: WEZ)

The direction of travel has bucked the trend, though

Wesizwe Platinum has released a trading statement for the year ended December 2023. The bad news is that the company is still loss-making. The good news is that the losses have decreased, unlike most PGM groups that had a worse year in 2023 than 2022.

The headline loss per share has improved from -8.24 cents to between -0.95 cents and -1.77 cents.

Little Bites:

- Director dealings:

- The CEO of Fortress Real Estate (JSE: FFB) bought shares worth nearly R1.9 million.

- An executive director of Argent (JSE: ART) has sold shares worth R258k.

- Cash company Trencor (JSE: TRE) has released results for the year ended December 2023. The group is essentially sitting on a pile of cash that will be distributed to shareholders once the group is able to do so. The total net asset value per share increased from R7.40 to R8.13 over 12 months. The share price is R7.00.

- There’s another leadership change at Bytes Technology (JSE: BYI), with non-executive director Mike Phillips stepping down with immediate effect. He was Audit Committee Chair. The announcement isn’t explicit on whether this relates to the ridiculous lack of governance around the ex-CEO’s share trades, or something else.

- Astoria (JSE: ARA) released the “information note” for the deal to acquire more shares in Leatt, which would take Astoria’s stake in the company to 8.84%. This is a Stock Exchange of Mauritius requirement that simply gives more information about Astoria, as the company is proposing the issue of new shares to settle the acquisition of Leatt shares. For those interested, it’s available here.

- Adcorp’s (JSE: ADR) odd-lot offer has closed. The company repurchased a total of 73,701 shares. This is only 0.07% of shares in issue, yet it takes 6,955 holders off the shareholder register for a total investment of R296k.

- Hammerson (JSE: HMN) has confirmed that its final dividend for 2023 will be translated into rands at a rate that results in a gross dividend of 18.66017 cents. There is a dividend reinvestment plan available for those who prefer to obtain more shares rather than cash.

- There is yet another delay in the Conduit Capital (JSE: CND) disposal of CRIH and CLL to TMM Holdings. Approval from the Prudential Authority remains outstanding, with the parties agreeing to extend the fulfilment date to 30 April 2024. This has been going on for a long time now.