This article is an adaptation of pieces I wrote in the weekly Ghost Mail publication during the peak of IPOs in 2021. It was uploaded a couple of weeks before we launched the new Ghost Mail so the share price CAGRs below are slightly outdated, but it’s the principle that matters.

My long-standing readers and followers on Twitter will be aware that I avoid Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) like the plague. Hype may be great for boxing matches and championship-deciding Formula 1 races, but it is highly dangerous in the world of investing. Nothing gets more hype in the market than a new listing.

An IPO is the process of a company listing on a stock exchange and raising capital. In addition to the company issuing new shares to investors and putting the proceeds in the bank account, the pre-IPO holders will often make a portion of their shares available for sale. This is to create “liquidity” and “shareholder spread” which simply means that there will be enough different shareholders to create a market for the shares and drive trade.

The most important thing to remember about IPOs (especially in the United States) is that the public markets are frequently used to facilitate an exit for previous investors like private equity funds or even the founders.

Now, they aren’t going to sell you the shares at what they perceive to be a bargain, are they?

Trust me, the bankers and venture capital (VC) firms know more than you do about the company. They are only willing to cash out or even dilute their holdings once the best days are over. The super-profits have been made by the time a company comes to market, so paying a valuation as though the company can keep growing like a startup is an almost guaranteed way to blow up your portfolio.

An IPO that only facilitates trade rather than the raising of fresh capital is known as a “direct listing” – examples include Coinbase, Roblox, Palantir, Slack and Spotify. Here’s a quick look at the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) at time of writing this article and the listing date of each of these companies:

- Spotify -1.3% (3rd April 2018)

- Slack +7.8% (20th June 2019)

- Palantir +19.1% (29th September 2020)

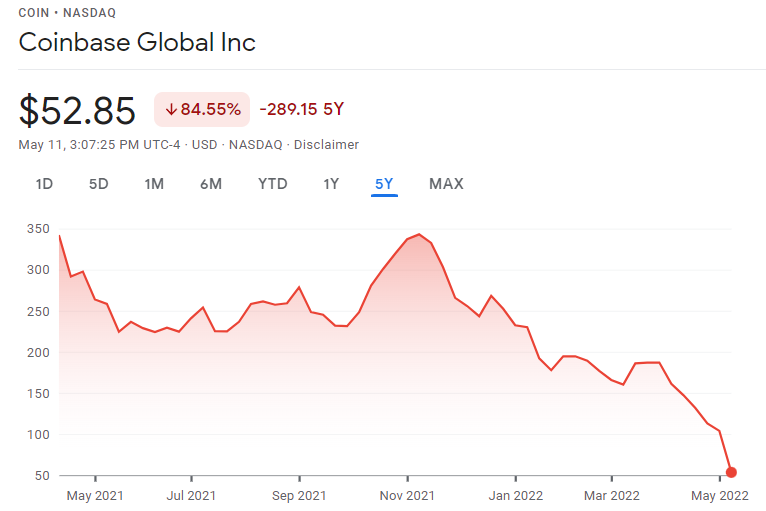

- Coinbase -55.1% (14th April 2021)

- Roblox -36.4% (10th March 2021)

This is a small sample size of course, but there’s a clear trend here and it won’t look any different with more examples: new listings generally suck for investors and the listings in 2021 were the most dangerous.

Buying IPOs at a time when the market is clearly expensive is a very painful mistake that you need to avoid.

IPOs ARE FAIR-WEATHER FRIENDS

If you draw a long-term chart of the number of IPOs each year in the United States, you’ll notice that they tend to peak at the end of a bull market. This isn’t by accident and isn’t a coincidence.

If you are bringing a company to market and hoping to attract investors, wouldn’t you want to do it when the market is hot and investors are itching for the next opportunity? Trying to sell something new to battered investors is much tougher than just taking advantage of hype around a specific sector or concept.

This is why you tend to see a flurry of IPOs in specific sectors at different times. For example, electric vehicles have been all the rage. The tech sector in general was flying throughout the pandemic. In 2022, things have cooled off considerably. The downstream impact on venture capital is becoming visible now, with a definite risk-off approach coming through from tech investors.

IPOs LOVE ASSET PRICE BUBBLES

When you hear stories of pimply kids from Harvard raising gazillions of dollars with little more than a one-page term sheet and a promotional video to explain the idea, you need to be afraid. In that environment, people might even start buying JPEGs of monkeys for enormous amounts of money. Oh, wait…

For me, NFTs must be the single best example of what happened to the market during the pandemic. The NFT market is collapsing and it’s going to get worse. Crypto is looking very shaky right now.

Unprecedented levels of economic stimulus (money printer go brrrrrr…) by the Fed created a spectacular asset price bubble. In those scenarios, there is plenty of money to be made provided you recognise the risks and realise that you are in a game of musical chairs. When the music stops, you need to have already cashed out.

In such a market, there are several IPOs every week.

For context, Statista tells me that there were a total of 685 IPOs in the US from 2016 to 2019. There were 431 just in 2020 and a whopping 951 in 2021, far more than in any prior year.

Another sign of trouble was the number of Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) that listed. These are “blank cheque” companies that raise money based on a loose plan to go off and do deals.

We have a similar mechanism on the JSE, though we haven’t seen a SPAC listing in a long time. Capital Appreciation Limited was the first SPAC on the JSE and has worked out very well, with a market cap at time of writing of nearly R2.4 billion and an exciting strategy in various FinTech verticals.

LOOKING BACK: COINBASE

In the process of migrating my work to the new Ghost Mail platform, I worked through many of my earlier blog posts in my life as a ghost.

In April 2021, I wrote about crypto exchange Coinbase. I specifically wrote about how I felt the company was a gigantic bubble, with IPO pricing that would hurt investors while maximising returns for those leaving the building.

Since then, Coinbase’s share price has more than halved.

Many investors made the argument at the time that Coinbase is the shovel in the gold rush. This is a great analogy that reminds us of the power of being a platform business. When selling the shovels, you don’t care if the buyer finds gold or not. That is the buyer’s risk, while your profits from the shovel sit safely in your bank account.

Of course, if nobody ever finds gold, then your shovel business is in serious trouble. That’s a longer-term problem.

Coinbase takes a percentage of the value of crypto traded on the exchange. In other words, the profits fluctuate with the pricing of crypto tokens. This isn’t the shovel in a gold rush; this is a share of the gold itself. As I wrote at the time, the analogy was being applied incorrectly.

A careful read of the prospectus (the detailed document that accompanies any listing) would’ve revealed that the company’s goal is to operate at break-even (!) for the time being. They were looking for investors who believed in the mission and would hold through cycles.

Sure. We all want that, along with a Ferrari for our next birthday present. Who wouldn’t want investors that don’t care about making a profit?

At the time of the IPO, Coinbase was priced at a forward Price/Sales multiple of around 9x. The Nasdaq (itself a listed company) was trading on a revenue multiple of 4.7x and makes a profit. The JSE was trading at a revenue multiple of around 4x.

So here was Coinbase, priced at double the revenue multiple of the traditional equity exchanges and aiming to simply operate at break-even. That wasn’t a story I was going to invest in.

I’m really glad I didn’t, as this chart will demonstrate:

IPOs are best avoided. Be careful out there, Ghosties.

What about IPOs offered in Property, are they also a no-show?

With IPOs it always depends on the facts. So tech IPOs during a tech boom are a worry, but a random IPO should always be assessed on its merits. The nice thing with property is that the value typically doesn’t stray too far from the net asset value (NAV) per share, which makes it a bit easier to assess.

Hey Ghost – the last true IPO on the JSE was in 2012, so you have got what you wished for… we have lost a net 79 companies since then too. So no IPOs, fewer listed companies, diminished investment universe – please square that circle for me?

Not sure about 2012 – I think there are many examples since then! But the delisting trend is clear and that’s mainly a liquidity problem in smaller caps, not necessarily an issue with IPOs. If they were priced reasonably, they would get more support. For as long as bankers use to-of-the-cycle IPOs to try palm off overpriced stock to investors, the IPOs themselves won’t be attractive. Difficult one because we all want to see more companies on the market, but nobody wants to see retail investors down 50% because they bought the hype.

Goes to the definition – a true IPO involves a registered prospectus and an open offer of shares to the general public. All new JSE listings since 2012 (less than half raised money) have either been restricted offers or private placings. 2012 was the last time Req 5.18 of the listings requirements was applied. The general public has basically been shut our of primary capital raisings on the JSE for over a decade.

Thanks for clarifying – I guess the B-BBEE structures are probably the major exception to that. You’re right though – and the bankers do it because it’s so much easier to raise the money from a handful of institutions rather than the public. I haven’t looked at the spread rules in a long time but perhaps there’s room for change there, carving out a percentage for smaller shareholders.