US Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi caused something of a stir in international relations a few weeks ago when she visited Taiwan. Chris Gilmour gives us more context to the international importance of Taiwan.

Pelosi’s trip was the highest-ranking visit by a US Speaker since Newt Gingrich in 1997 and appears to have taken place without President Joe Biden’s express permission. The visit has caused major problems for US/China relations, which were already at a low ebb and in retrospect, it should probably not have happened. But it did, and the US and its allies in the far east will have to live with the economic and geopolitical consequences for quite some time. Already, China has sent a barrage of ballistic missiles over Taiwan, some of which landed in Japan’s territorial waters.

So, what’s the big deal about this little island, formerly known as Formosa? Why are the Chinese so obsessed about bringing it back into the fold?

The right to exist

China has never recognized Taiwan’s right to exist as a separate state, preferring to regard it as a renegade province that someday will be re-incorporated into China.

Taiwan has been ruled by various countries and dynasties over the centuries but its most recent history dates back to Japanese occupation in the late nineteenth century. In 1895, Japan won the First Sino-Japanese War and the incumbent Qing government had to cede Taiwan to Japan. After World War II and Japan’s unconditional surrender to the Americans, control of Taiwan and all territories it had taken from China were relinquished by Japan. The Republic of China (ROC) under the leadership of Chiang Kai-Shek and his Kuomintang began ruling Taiwan with the overt approval of the main western allies, the US and UK. However, a few years later, civil war broke out in China, and Chiang Kai-shek’s troops were defeated by Mao Zedong’s Communist army. Chiang, the remnants of his Kuomintang government and their supporters – about 1.5m people – fled to Taiwan in 1949.

Today, and for many decades, there has been confusion about what Taiwan is. Technically, it has its own constitution, democratically-elected leaders and about 300,000 active troops in its military. In 1971, the United Nations stopped recognizing the ROC as the legitimate Chinese power and instead recognised the People’s Republic of China (PRC), also known colloquially as “Red China” due to it being run by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Only around 15 countries formally recognize Taiwan today as a fully independent country.

China offered an olive branch to Taiwan some years ago in the form of a “one country, two systems” proposal, which would have allowed Taiwan significant autonomy but always under the ultimate control of Beijing. It would have been very similar to Hong Kong’s status.

Taiwan rejected this option.

Strategic ambiguity

America’s long-standing policy has been one of “strategic ambiguity” to the extent that it would intervene militarily if China were to invade Taiwan. Officially, it sticks to the “One-China” policy, which recognises only one Chinese government – in Beijing – and has formal ties with Beijing rather than Taipei. In the unlikely event that China and Taiwan were eventually to agree peacefully to re-unite in future, the US would likely endorse such a move. But it has also pledged to supply Taiwan with defensive weapons and stressed that any attack by China would cause “grave concern”

To the casual observer, China is a formidable player on the world stage. After all, it has risen to become the world’s second-largest economy after the US in a matter of a few decades. But that extremely swift ascent has disguised some major vulnerabilities. So although China is the 6th largest oil producer in the world, such is its insatiable appetite for energy that it imports 80% of its oil. On the food front, things are even worse, with the country importing 85% of its food.

Under the old pre-coronavirus conditions, when Pax American and unfettered globalization were still apparent, this wasn’t a problem. Most countries stuck to the rules and technology helped to drive down the prices of consumer goods around the world.

But things have changed in the new post-pandemic era. The levels of bellicose rhetoric surrounding many territorial issues such as Taiwan have risen significantly. Three years ago, who would have thought that the US would leave Afghanistan to the tender mercies of the Taliban once again or that Vladimir Putin would physically invade Ukraine?

But both of these events have occurred, less than a year apart.

Huff and puff

Once again, the casual observer might be forgiven for thinking that China might well up the ante and invade Taiwan. But although it has been huffing and puffing away furiously for the past few weeks since Pelosi’s visit, the chances of a near-term invasion of Taiwan are virtually nil, in my humble opinion.

The first point to note is that Putin and the Chinese leader Xi Jinping met at the opening of the Beijing Winter Olympics back in early February. It is inconceivable that the pair didn’t discuss Russia’s intended invasion of Ukraine, which at that time was only a few weeks away. Both men hold the west in contempt, believing liberal democracies to be fundamentally weak and ineffectual. And America’s hasty withdrawal from Afghanistan did nothing to dispel that notion. They must have thought, quite reasonably given what had happened in Afghanistan, that America and the west would not lift a finger to help Ukraine if a full-scale invasion was mounted.

After all, there was hardly a murmur from the west after Russia annexed Crimea and the Donbass region of Ukraine back in 2014. That being the case, Ukraine would be a blueprint for a Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

However, nobody could have foreseen either the degree of cohesion adopted by the west when it came to applying sanctions against Russia, or the catastrophic failure of the Russian army to overrun Ukraine. To date, over 1,000 western companies have left Russia, the majority of them being unlikely to ever return unless there is significant regime change in the country. While Putin had established a sizable war chest with which to sustain his offensive – some estimates go as high as $600 billion – much of that was frozen in foreign bank accounts near the start of the conflict. Six months into the conflict (which was supposed to have only taken three days!), Russia now finds itself bogged down in a grinding stalemate that has no end in sight.

Xi must have got a massive skrik, as they say in Afrikaans. The last thing any Chinese leader needs is comprehensive sanctioning from the west, either in terms of import or exports. China has been manifestly unable to convert from being a manufacturing, export-led economy to a consumer-oriented economy. It is vitally important that Chinese exports to the west remain free of sanctions and it is equally important that no blockades of oil or food occur.

The Malacca dilemma

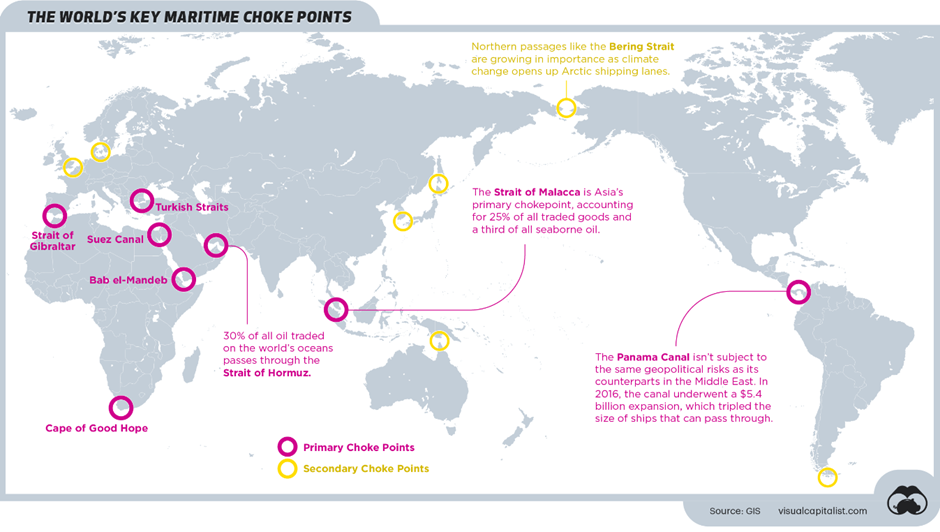

This is where China’s relative geographic isolation becomes all too painfully apparent. In terms of oil reaching China, it has to navigate two “choke points” – the Straits of Hormuz in the middle east and the Malacca Strait (a 1.5 mile natural seaway) – that joins the Indian and Pacific Oceans. If China invaded Taiwan, the so-called QSD alliance countries of the US, Australia, India and Japan might well feel obliged to mount a naval blockade against China. Even if an oil tanker manages to get past a naval blockade of the Straits of Hormuz, the Malacca Strait is a really problematic choke point with no really viable alternative, apart from travelling in the notoriously treacherous Southern Ocean beyond Australia and New Zealand.

On the east side of Malacca Strait, notably in the South China Sea, China has been exerting huge influence in recent decades, even going to the extent of constructing artificial islands bristling with weaponry to let all other countries know that this is their bailiwick. China routinely objects to any action by the US military in this area. Other countries, such as the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan and Brunei, claim all or part of the South China Sea, through which approximately $5 trillion in goods are shipped every year.

China has also offered to cut a canal through the Isthmus of Kra in Thailand that would not only cut the time between the Indian and Pacific Oceans by much more than going through Malacca but it would then be under China’s control and would no longer be a dangerous choke point. However, this radical proposal has not met with approval from Thailand.

The risks associated with having to contend with a naval blockade of oil and food are probably too great for China to bear. It is thus highly unlikely that China will dare to invade Taiwan while it is still so vulnerable to having its lifelines literally cut off.

However, in typically Chinese long-term thinking ahead fashion, successive Chinese administrations have been exploring the possibilities of securing alternative non-maritime routes for import and export. The Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) is part and parcel of that and whilst it hasn’t been as successful as originally envisaged, it nevertheless has the potential to become a significant component of trade over time.

The biggest single beneficiary of the BRI so far has been the port of Guadar in Pakistan, a long-time ally of China. If the Straits of Hormuz were ever to be blockaded for Chinese shipping, it is not inconceivable that ships carrying oil bound for China could offload onto road tankers at Guadar and make the long journey overland to China via the Karakoram Highway, that was conveniently financed by the Chinese some years ago.

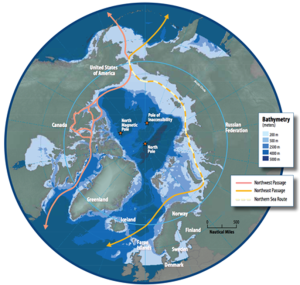

But there is another, highly radical possibility opening up to China as the world’s oceans warm up thanks to climate change. The Northern Sea Route is slated to become ice-free as early as next decade, which will allow China to access vast quantities of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Yamal in northern Russia. Currently, logistics make it costly and ineffective for China to access large quantities of LNG from Russia but if a new, permanently navigable sea route with no choke points were to open up, that would change the dynamic entirely.

Russia and China are neighbours. It makes sense from so many perspectives for the two countries to trade much more freely with each other. Russia is the world’s biggest supplier of energy, while China is the world’s biggest user of energy. But pipelines don’t just materialise overnight, especially not those in the permafrost of Siberia, where most Russian oil and gas is located. Russia desperately needs to keep pumping its oil, even if it does so at a steep discount to customers such as China and India, because if it stops pumping, the oil will freeze in the pipes and associated infrastructure of Siberia and there are no longer US oil engineers to keep that infrastructure maintained. There isn’t a convenient far eastern Russian port that can handle vast quantities of oil and gas and ship them quickly and efficiently to China, so the opening up of the North Sea Route would be extremely advantageous to both China and Russia.

So, the visit by Tannie Pelosi to Taiwan has set off all sorts of delicious possibilities for geopolitical analysts to consider.