Securing a fair and certain purchase price for a business can be a challenging negotiation, fraught with uncertainties and risks for both buyers and sellers. One mechanism that has gained prominence for bringing clarity and certainty to this process is the “locked box” price determination method. Despite its growing use, the process often remains misunderstood and shrouded in confusion. What exactly does it entail, and what fundamental principles should parties grasp when negotiating a locked box transaction?

Typically, the locked box concept involves the seller guaranteeing (or warranting) the business’s balance sheet as at a specific date before the signing of the Sale and Purchase Agreement (SPA). This is a helpful starting point because the seller and buyer agree on a set of financial statements to determine the purchase price, and these accounts are warranted as part of the transaction. However, the locked box mechanism extends beyond simply agreeing on and warranting these financial statements.

Let’s talk about (i) what’s in the “box” and (ii) what constitutes a “lock”. The box is essentially the value attributable to the business, and the lock refers to pegging the price for that value at a specific date. The next question is why would one want to lock the box? And there are a few answers:

(i) the seller has decided to dispose of the asset and wants the price to be pegged at an agreed date as the seller has made the decision to exit and walk away from the value of the asset at that point in time;

(ii) the transaction may not be capable of immediate implementation due to certain consents and regulatory approvals which may be required, but the seller and purchaser have already decided to sell and to buy and are willing to let go, on the one hand, and assume on the other hand, risk and reward in and to the asset with effect from the locked box date;

(iii) in a competitive environment, a locked in price is king; and

(iv) the purchaser will receive a business (pretty much) in the same position in which it found the business when it conducted its due diligence.

The parties to the transaction will, therefore, have agreed to “lock the box” at a point in time from a financial perspective, such that the price payable for the business is tied to the date on which the box is locked (often called the locked box date). The seller has agreed to lock in the value of the business as at the locked box date and to deliver to the purchaser a business on the completion date which is as close as possible (other than ordinary course of business operations) to the business as it was on the locked box date.

Hence, the fundamental concept of a locked box is to deliver to the purchaser a business on the completion date which is identical to the business on the locked box date, save for ordinary course trading. The purchaser, in agreeing to the locked box, is relying on the management team and existing shareholders to operate the business in the ordinary course, such that what was promised to it on the locked box date is what it actually receives on the completion date. There are many contractual guardrails included in a locked box transaction to ensure that this position is achieved on implementation (see below). Of course, it is accepted that if, in the course of conducting the business in its normal and ordinary course, there are negative impacts on the business, the purchaser assumes this risk. The converse is also true, where all reward arising from the conduct of the business is for the purchaser’s benefit.

How do I protect myself as a purchaser in a locked box transaction?

A purchaser is not just expected to “take the seller’s word” that it will deliver the business in the same form on the completion date as it was on the locked box date; all necessary protections will be included in the legal agreements. Such protections include:

1. robust interim period undertakings between the locked box date and the completion date, in terms of which the seller will confirm that it has and will operate the business in the ordinary course and will not take any actions which are outside the ordinary course of business with effect from the locked box date until implementation, generally referred to as the locked box period;

2. termination rights in the event of a material adverse change (or MAC event) occurring; and

3. any value leakage, commonly referred to as leakage. With the undertaking to operate in the ordinary course of business often comes a right given to the purchaser to terminate the agreement if any of these undertakings are breached and/or the breach results in a material loss to the business.

What is “leakage”?

Leakage is any outflow of cash, assets or other value from the business to or for the benefit of the then existing shareholders or their associates and related parties during the locked box period. In essence, it captures amounts that are extracted from the business that diminish its value (i.e. breaching the principle of locking in the value) which are not ordinary course matters. This value extraction will reduce the price payable by the purchaser to the seller for the business.

Bearing in mind that the base principle is to deliver a business which is almost identical on the completion date to that which existed on the locked box date (subject to ordinary course impacts and movements), the concept of leakage should always be in keeping with this principle. So why then is leakage not just the incurrence of any expenditure outside the ordinary course of business, and why is it (more often than not) specifically linked to value extraction to shareholders?

The starting position and understanding of the parties is that the business will be conducted in the ordinary course (as captured in the robust interim period undertaking regime linked to the termination right). Therefore, the concept of leakage is an additional protection to ensure that shareholder value extraction, which has no benefit to the business and which actually detracts from its value, reduces the price (rather than giving the purchaser a termination right). Parties to the agreement are able to agree any definition of leakage they wish, which can include known once-off items that should reduce the price and, generally, the market determined principles applying to leakage will be linked to shareholder value extraction (in any form).

What then is “permitted leakage”?

Permitted leakages are those specific items which would have constituted leakage but for the parties agreeing that they will not, and which are permitted to be made without reducing the price. These items may, for example, include specific bonus payments which are not paid in the ordinary course, specific spend on items that are outside the ordinary course but agreed to between the parties, dividends that are required to be declared pursuant to the transaction, deal facilitation payments, or any other deal specific matters. Without including these items in the concept of “permitted” leakage, they would otherwise fall within the definition of leakage and result in a price reduction. The definition of permitted leakage need not refer to payments in the ordinary course of business, but parties often include these matters for clarity or psychological safety, as it is not legally necessary.

What is the upside for the seller?

Subject to the purchaser calling a MAC event or terminating the agreement for a breach of interim period undertakings, the seller is guaranteed a value for their business as at the signature date of the agreement, regardless of the movements to cash, debt and net working capital (subject to leakage), provided they run the business in the ordinary course during the locked box period. In addition, as typically provided in a locked box transaction, “risk and reward” in and to the business passes to the purchaser with effect from the locked box date, and a ticking-fee is charged on the locked box price to compensate the seller for:

(i) the time value of money, as they would have actually received payment on the locked box date, save for regulatory and other conditions precedent (versus when they will actually receive the price, being a few months later); and

(ii) any cash generation in the business during the locked box period, from which the purchaser will now benefit, post completion (even though it was not running the business).

The ticking fee is generally charged with reference to an interest rate linked to prime and will be added to the equity value, or could simply be an agreed per diem rate and form part of the final price payable. In some instances, the parties will agree a ticking fee linked to the cash generation expected in the business during the interim period.

So, what is the price formula in a locked box transaction?

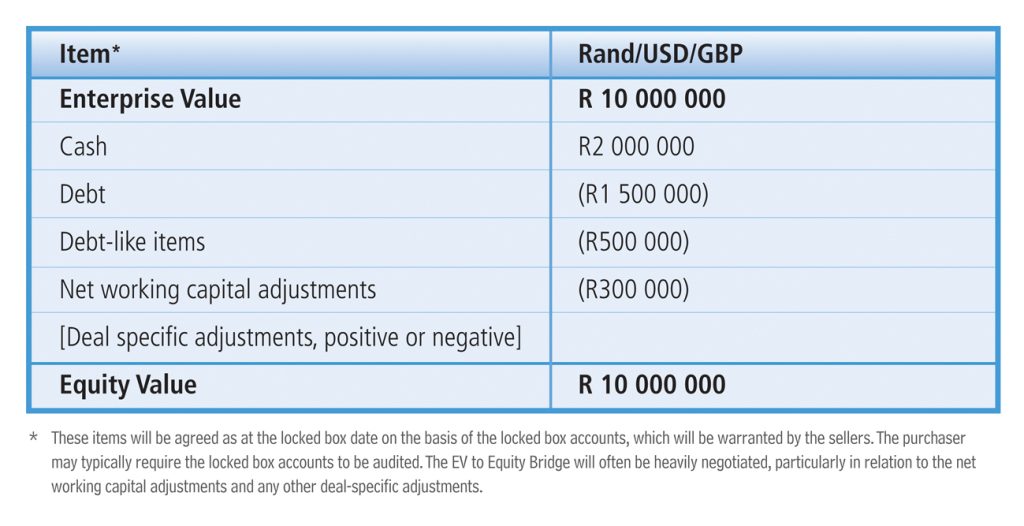

The price formula that should be included in a sale agreement for a locked-box transaction should be simple in nature, as the parties would have done the hard work in agreeing the EV to Equity bridge and the various inputs prior to signing the sale agreements. A typical locked box price formula will be as follows –

(i) Equity Value (as agreed in the EV to Equity Bridge); less

(ii) Leakage (which will exclude Permitted Leakage); plus

(iii) the Ticking Fee Amount.

Agreeing the equity value to input into the sale agreement is for the parties and their advisers to determine, and while the inputs will be deal specific, the table below sets out a basic EV to Equity Bridge.

Should I agree to a locked box?

Before agreeing to a locked box transaction, ask yourself:

(i) am I buying or selling?

(ii) is this the kind of business with material fluctuations in working capital (including stock values) that would justify a relook at the numbers before closing?

(iii) will the locked box period likely be a busy or slow period for the business (i.e. as seller will I be giving up too much value or as buyer will I be overpaying based on where the business is likely to be on completion)?

(iv) do I trust management to run the business in the ordinary course?

(v) do I want certainty on the price I will be receiving for the business?

(vi) do I want certainty that the value I agreed to pay for the business will actually be the value on the payment date?

Whether or not locking the box is right for your transaction will depend on the nature of the business being sold and where the negotiating power sits between the seller and the purchaser. Regardless, before agreeing to lock the box, the fundamentals set out above should be kept in mind so there are no surprises when negotiating the sale agreement.

Lydia Shadrach-Razzino is a Partner and Kaylea Sher-Fisher a Senior Associate in M&A | Baker McKenzie (Johannesburg).

This article first appeared in DealMakers, SA’s quarterly M&A publication.

DealMakers is SA’s M&A publication.

www.dealmakerssouthafrica.com