Last week, Chris Gilmour took a detailed look at the non-discretionary retailers on the JSE. This includes the grocery stores and pharmacy chains. This week, the focus is on the discretionary retailers, which would include clothing, furniture and perhaps some DIY too. In part 1, Chris focuses on Woolworths.

Included in the discretionary retailer universe are three clothing retailers (Truworths, Mr Price and The Foschini Group), a hybrid clothing and food retailer (Woolworths), a retail conglomerate (Pepkor), a furniture retailer (Lewis Group) and a DIY / Home Improvement retailer (Cashbuild).

What is notable from the outset is how poorly most of these retailers have performed in the past five years on a relative basis, with a few exceptions such as Lewis and Cashbuild. With Woolworths, the pain has largely been self-inflicted with the ill-conceived acquisition of David Jones in Australia. The same goes for Truworths, a really good and well-managed business but one that has a slavish adherence to credit and nothing else. Two retailers, Mr Price and The Foschini Group (TFG), deserve special mention for expanding into the pandemic-induced downturn, rather than just accepting their fate. That strategy is now paying off handsomely for both.

| Price | Market cap (R’bn) | Price / Earnings multiple | Revenue (R’bn) | HEPS (5-year CAGR) | |

| Woolworths | 5380 | 56.3 | 19.1x | 78.8 | -3.85% |

| Mr Price | 18316 | 49.3 | 14.3x | 28.1 | 7.60% |

| Pepkor | 1970 | 74.6 | 12.8x | 77.3 | n/a |

| TFG | 12346 | 41.1 | 12.2x | 46.2 | -1.53% |

| Cashbuild | 25300 | 6.5 | 10.3x | 12.6 | 8.70% |

| Truworths | 5218 | 22 | 8.3x | 17.5 | -4.81% |

| Lewis | 4980 | 3.1 | 5.9x | 7.3 | 16.2% |

Woolworths

Probably the most well-known (and loved) discretionary retailer in SA is Woolworths (Woolies). Based unashamedly on the Marks & Spencer (M&S) brand in the UK, it has been around in SA since the 1930s.

Woolworths management should exit Australia, not just David Jones, and demerge the food and clothing divisions in South Africa into two separate companies. The real beneficiary of this would be the shareholders, who over the past 5 years have experienced substantial value destruction. And despite strong rumours circulating in Australia that Woolworths is indeed considering selling David Jones, the company itself continues to deny this speculation outright.

The plan with David Jones when it was originally purchased was to increase the own-branded portion of the merchandise offering, do more direct sourcing and achieve better stock management with improved information systems, which would in turn increase the gross margin and double the net margin over the following few years. It all sounded like good retailing. Effectively, as management said at the time, they were going to take the Woolworths concept to Australia, using the David Jones brand. Marks and Spencer had worked in the UK, particularly the food offering amongst some strong competitors, so it would seem that Woolworths could do the same in the Southern hemisphere.

That is not what happened in our view. In reality, what happened was almost the opposite. At a time when the department store format around the world is in decline it would seem that Woolworths brought the David Jones department store format to South Africa, turning the clothing, beauty and home business into a department store, which in turn is now struggling.

Woolworths South Africa has for many years had a close relationship with M&S. The two companies have shared suppliers, sourcing skills, technology, product strategy, branding strategy and used to provide graduate trainees with opportunities to work in each other’s companies. If you were to walk into a Woolworths Store in South Africa, you would be forgiven for thinking you were in a Marks and Spencer store. Even the last chairman of Woolworths, Simon Susman, who used to be CEO and head of Foods, has family connections to the founding family of Marks and Spencer.

But we believe that due to the close connection, as well as other factors the businesses are more alike and face similar threats. Due to the competitive nature of the UK retail market, M&S has, we believe, faced tough times sooner than Woolworths. Additionally, Woolworths has been one of the main beneficiaries of the demise of Edgars and the wider Edcon group. This has plastered over the real devastation that is occurring in the retail market for not just Woolworths but other retailers too.

The signs are now there that Woolworths is facing a critical period in its history.

Woolworths South Africa used to be part of a larger retail group, called the Wooltru Group. This retail group included Massmart and Truworths as well. The Wooltru group demerged the subsidiaries as the synergies that the management thought it could achieve were not being achieved. The group had outgrown itself. Investors wanted focused investment and we believe the same still applies today.

In our view, there are no synergies or rationale to keep the food business tied to an ailing department store in Australia and a struggling quasi-department store in South Africa. Investors would most likely value the food business higher if it were not encumbered by the rest of the companies within the group, from which it gains in our view no synergies or benefit.

There is no reason why the Foods business should be retained within the larger clothing retail group, especially since food has been removed from the Australian retail offering. A focused food retailer with the market positioning and customer profile of Woolworths Foods would become one of the most highly rated retail companies in South Africa. As top line growth slows and cash generation increases, it could become a haven for investors in a time when the economy is starting to slow, much the same as the Clicks Group

Woolworths Foods is a hugely aspirational and iconic brand in South Africa and that brand equity has been established over many decades of delivering ultra-high quality foods without ever compromising standards. But new space growth has been tapering off in recent years, with no apparent new growth vector in sight. In a South African economy that is likely to languish for the foreseeable future, our base case scenario is for Foods to become a cash cow for the rest of the business.

This is the least troublesome part of Woolworths’ business and has been so since the company’s genesis. While the clothing division has often got it wrong with respect to fashion, Foods has just kept pumping out healthy growth. However, it may be reaching saturation in a languishing South African economy with no obvious new meaningful growth vectors in sight.

It has always resonated with upmarket shoppers, as it has got the mix right in its stores. The layout is also very clever; shoppers invariably have to walk through the clothing part to get to Food and in the process are susceptible to cross-shopping opportunities.

Back in the mid 2000s, when Simon Susman was CEO, Woolies Foods embarked upon an extensive rollout of standalone convenience stores. And while a number of these stores undoubtedly cannibalised existing stores in close proximity, the fact that the background economy was growing reasonably well meant that lost market share was soon recouped by the cannibalised store.

It is current management’s aim to concentrate its efforts on locating any new retail space in larger shopping centres. This despite the obvious trend that has emerged since the Covid lockdown of consumers preferring local shopping.

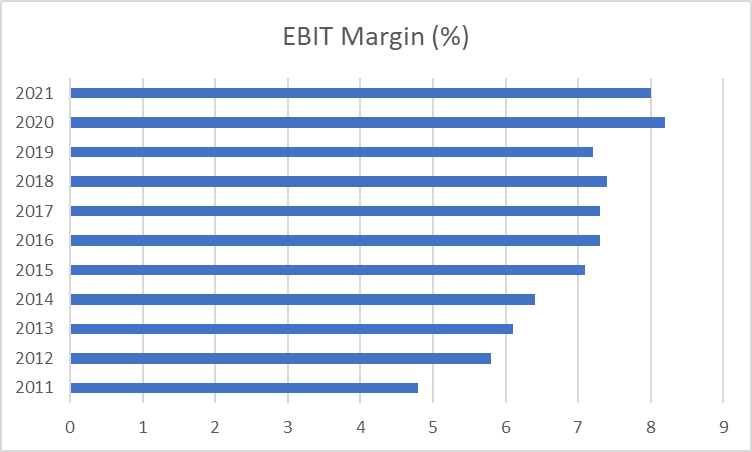

Profit margin appears to have plateaued

Ten years ago, in financial 2011, operating profit margin was a relatively low 3.8%. Throughout most of the last decade, this margin increased consistently, as the new store rollout programme matured and as previously franchised businesses were converted to Woolies Food corporate stores. In financial 2021, operating margin was 8% and appears to be stabilising at around that level. Gross profit margin has been very steady between 23.5% and just over 25% in the past decade.

With very little new space growth likely to materialise in the next few years, margins are likely to remain at or around current levels.

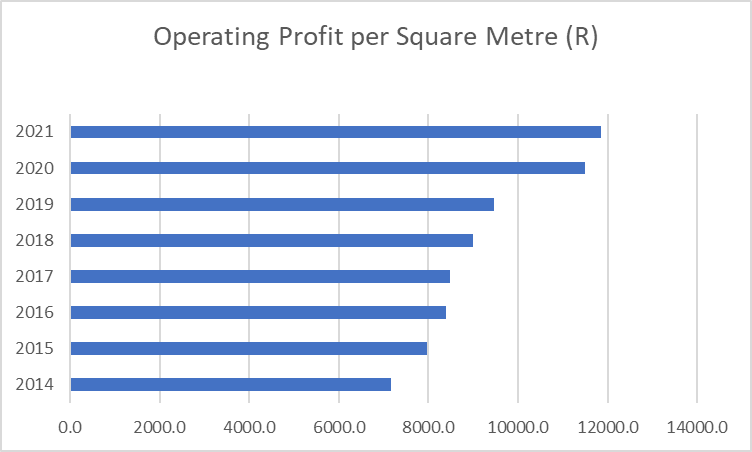

The ability of Woolies Foods to profitably exploit its existing floor space is demonstrated in the following chart of operating profit per square metre. There is a very satisfying upwards trajectory, which has improved noticeably in the 2020 financial year, as square metreage stayed fairly constant.

A league apart when it comes to quality

For many decades, Woolies has been in a league of its own when it comes to high quality food shopping. Other than a handful of specialised independent stores and upmarket Spars, the competition has largely left Woolies’ traditional stomping ground alone. Pick n Pay tried competing on the convenience format not long after Nick Badminton took over as CEO but that challenge didn’t last long, as it was unable to cement long-lasting supplier agreements to supply high-quality convenience and other meals. More recently, Checkers has entered the fray with a degree of success, albeit with an as yet limited offering.

Woolies’ dominance of the convenience food market is based on their ability to source a good range of exclusive suppliers and retain them but also to be able to supply their stores with these items at precisely the correct temperature. It has taken many years to attain this status and new entrants will find the going difficult if they wish to compete.

Often, Woolies’ relationships with its suppliers go back many decades and are established literally with a handshake. Woolies insists on exclusive supply relationships with its suppliers, so there is no possibility of a Woolies’ supplier also supplying Checkers for example, other than in the mainstream national brands arena.

However, a relatively new incipient threat to Woolies’ traditional dominance of the convenience food market may lie in the recent phenomenon of recipe boxes / meal kits. The leaders in the field in Europe and the UK are HelloFresh, Gousto and Mindful Chef but South Africa has recently joined in with operations such as Ucook, Takealot, Netflorist and Daily Dish springing up. Admittedly Woolies has risen to the challenge with its own range of recipe boxes but not surprisingly they tend to be more expensive.

Woolies Foods dominates private label food capacity in SA

South Africa suffers from a dearth of food producers that are prepared to supply food retailers with own-brand or private label products. Woolies has certainly managed to grab the lion’s share of private label capacity in South Africa, with long-standing arrangements between itself and Rhodes Food Group, Libstar and Interfoods for example. Notable among the large local food producers that are unable or unwilling to participate in private label production is Tiger Brands. Tiger steadfastly refuses to produce private label on the grounds that by so doing it would dilute the value of their existing brands.

Home delivery

Home delivery is regarded as a loss leader for many retailers and Woolies is no exception. It may well find that outsourcing its home delivery completely to the likes of a Takealot would make more sense than persevering with in-house capability. M&S has achieved this in its relationship with home delivery specialists Ocado in recent years.

Rest of Africa not a serious proposition for Woolies Foods

The rest of Africa was a growth vector for a number of South African retailers post 1994, although that trend has reversed in the past couple of years, with Shoprite having exited a number of African jurisdictions. Woolies Foods has hardly ever ventured far into Africa, other than into the neighbouring states. To date, only clothing stores have been opened in the rest of Africa (apart from Botswana and Namibia), for the simple reason that the very low tolerance demanded by Woolies for chilled and frozen foods cannot be guaranteed in most African countries, due mainly to erratic electricity supplies.

Woolies can guarantee cold chain to the neighbouring states. If it were to go farther afield to the rest of Africa, it would be an entirely different challenge. So for example, Woolies could deliver certain frozen and long life products into the rest of Africa but they decided against it as they want to bring the full Woolies Food experience or nothing.

And former CEO Ian Moir made it quite clear when he made his ill-fated decision to buy David Jones in Australia: Woolies saw far more growth potential in Australia than in the rest of Africa.

Woolies Food market share is remarkably high

Market share among listed food retailers is estimated at around 10%, making it the smallest of the “big four” – Shoprite, Spar, Pick n Pay and Woolies. Woolies’ perceived grocery universe size is between R350 billion and R400 billion. According to management, market share is growing, though they won’t be drawn on exact numbers.

This is a remarkably high level of penetration, especially considering that Woolies Food is a very upmarket offering, operating in a developing country with the highest rate of persistent unemployment of any country in the world. To increase that market share meaningfully beyond the current level, given the likelihood of a languishing local economy appears highly ambitious.

Woolies’ price points are substantially higher than their competitors.

Woolies Foods price points are substantially higher than those of their JSE-listed competitors and are similarly priced to small-scale artisanal food producers. The reasons is simple: the quality of their foods is much higher than that available at the competition and Woolies’ fresh offering, for example, is preserved much better. For as long as the South African economy was showing even moderate growth, this wasn’t a problem, as Woolies shoppers tend to be willing to pay up for the kind of quality that is conspicuous by its absence at the other large retailers. But with the local economy likely to experience anaemic growth beyond the current year’s bounce-back from the Covid pandemic, the ability of Woolies Foods to carry on charging such ultra-premium prices may be reaching a tipping point.

At this point it is worth reflecting on a paragraph in the 2019 Marks & Spencer annual report:

“In 2018 we acknowledged that our Food business had become too premium and lost some of its broader appeal. While customers still recognised us for quality, the competition had worked hard to match our success by copying our innovation and fresh product ranges and we hadn’t kept up. The challenges were compounded by our outdated supply chain, with excessive waste, poor availability and high operating costs eroding our profits.”

Is Woolies facing similar challenges in SA? Obviously not in cold chain but perhaps in Woolies being perceived as too premium?

Woolies management realised that their pricing in certain categories was simply too high and have partially addressed the problem by significant investment in price in the past couple of years, notably in poultry products.

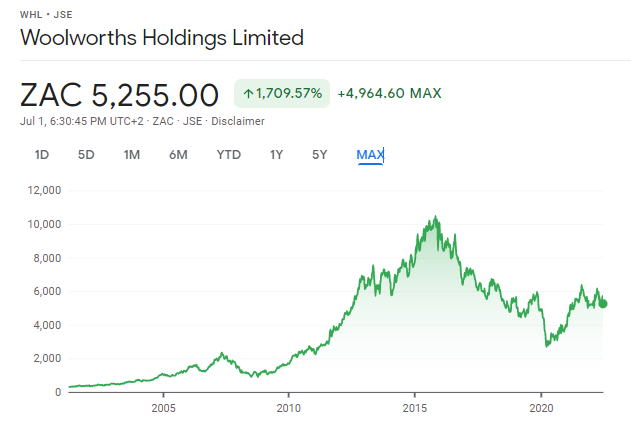

Although it may seem silly to draw such a long-dated share price chart, it does tell the story of this business in different economic conditions. Importantly, it also shows the value destruction after the acquisition of David Jones in 2014:

Thanks, most informative.