No rest for the wicked here, as Chris Gilmour unpacks the relative levels of infrastructure development in the emerging world vs. the developed world.

One of the areas that differentiates the developed world from the emerging world is the commitment to infrastructure development. The old developed world is largely stuck with aged, creaking infrastructure that hasn’t moved in line with increased population size, whereas the developing world, as proxied by countries such as China and Malaysia, tends to have far greater commitments to infrastructure development across the spectrum.

And the world’s largest economy, the USA, has one of the world’s worst infrastructural deficits.

Rectifying this situation with a much greater commitment to decent infrastructure spend is “good” investment and reaps all sorts of benefits over time. But neglecting it, even for a few years, can have catastrophic results.

The last really big federal project that the US government embarked upon (apart from NASA’s space program of the 1960s and 1970s) was the interstate freeway system that was constructed in the US from the late 1950s through the early 1970s. Since then, there has been very little of any consequence, and this is obvious to any non-US traveller arriving at the tawdry JFK airport in Queens in New York City. And the road leading into the city from the airport is buckled and mangled, a reflection of the poor maintenance it receives. The bridges across the East River are ancient and only the (relatively) recently constructed Verrazzano Bridge connecting Staten Island and Brooklyn is less than 50 years old.

US utility companies often struggle to keep the lights on and so-called “brownouts” occur, whereby voltage reductions are deliberately put in place to conserve electricity.

According to a fairly recent study by the highly respected American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), deteriorating Infrastructure and a growing investment gap will reduce US GDP by $10 trillion in 20 years. In a hard-hitting report released last year, the ASCE said that “Infrastructure inadequacies will stifle US economic growth, cost each American household $3,300 a year, cause the loss of $10 trillion in GDP and lead to a decline of more than $23 trillion in business productivity cumulatively over the next two decades if the U.S. does not close a growing gap in the investments needed for bridges, roads, airports, power grid, water supplies and more.”

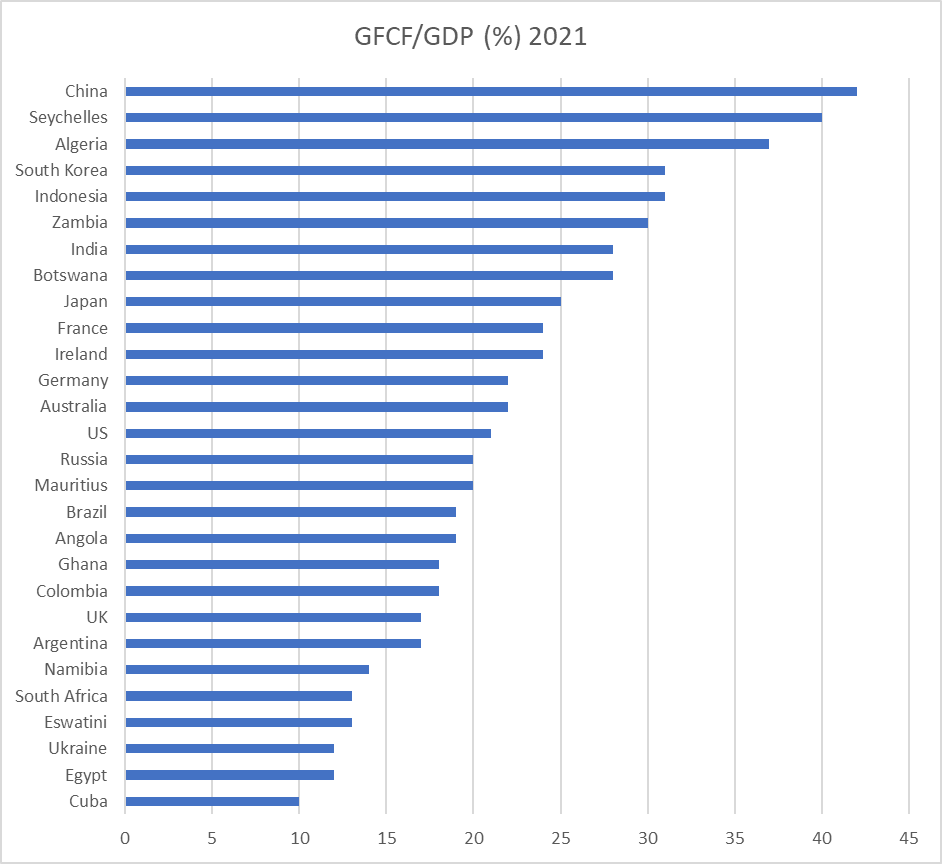

As a percentage of GDP, Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) in the US is a relatively low 21%, which places the US not much higher than Russia in the league table of infrastructure spend:

The UK (at 17%) is even worse and South Africa is a very low 13%.

Between now and 2039, the ASCE report estimates that nearly $13 trillion is needed across 11 infrastructure areas: highways, bridges, rail, transit, drinking water, stormwater, wastewater, electricity, airports, seaports and inland waterways. With planned investments in infrastructure currently totaling $7.3 trillion, that leaves a $5.6 trillion investment gap by 2039.

This gap has to be filled, and soon!

We are probably entering a new era in state spending globally, one that is going to be funded by substantially higher taxes. The party has been going on too long, with low taxes and little or no decent infrastructure spend. The end result is inevitable – decay and destruction of existing infrastructure.

Not long before he left office, Donald Trump signalled that his administration was intent on spending large amounts of money on new infrastructure. But it’s debatable that he fully grasped just what this would have entailed in terms of higher taxes.

Americans have become used to paying very little tax over the years and it will take a brave president to reverse that situation. But that is precisely what needs to happen.

Britain is in a similar position and if anything, its infrastructure deficit is even worse. A classic example is the rail network. Largely privatised from the late 1970s onwards, much of the rolling stock still appears to date from that era and even earlier. One of the biggest problems facing infrastructure development in the UK is a) the authorities’ obsession with mega-projects and b) concentrating almost all infrastructure development in London and the south-east of England. Some of these are vanity projects such as Crossrail in London, although the most recent large bit of infrastructure development relates to the new nuclear power plant at Hinkley Point in Somerset.

One of the things that struck me about the state of unreadiness of the developed world when the Sars-CoV-2 virus struck was the lamentable state of hospital and associated infrastructure. This was in stark contrast to how developing countries such as China attacked the situation, building pre-fabricated 1,000-bed hospitals from scratch in a matter of days. But if we use Britain as a proxy for the developed world, its infrastructure was found to be wanting, with the National Health Service (NHS) hospitals at or near breaking point most of the time. To be fair, the authorities did convert other buildings into so-called “Nightingale” hospitals but these were never used. But if we go back in time to 1968-72 with the Hong Kong flu pandemic or 1957 with the Asian flu pandemic, both of these events were easily coped with using existing hospital infrastructure.

The harsh fact of the matter is that health bureaucrats the world over believe that most healthcare problems can be solved via the application of technology, such as virtual doctor appointments etc.

The reality is that they can’t.

So, infrastructure development is likely to be a big factor in future high-level spending priorities if for no other reason than that existing infrastructure really is at the end of its tether. It will be interesting to see how this is paid for ultimately, over and above by higher taxes.