Few truisms ring as clear as “high-risk, high-reward” in finance. However, the adage should, in truth, read “higher reward requires higher risk” as risk needs, of course, not deliver returns; but the underlying message remains clear. To assume otherwise would be akin to ordering a free lunch. Despite this, the cost of reward lesson is sometimes forgotten when risk is ignored either through ignorance (where investors indulge in too-good-to-be-true investments) or through design (where clever financial engineering at times hides, without removing, risk – specifically of the systemic kind).

But perhaps it is possible to have one’s cake and eat it. The sweet spot is to construct an index that aims to preserve the upside while limiting the down. It turns out that lower risk doesn’t have to mean lower reward, as we show through our Satrix Low Volatility Equity ETF case study.

The Low-Volatility Signal

We define the low-volatility signal as a composite of price volatility and fundamental risk (e.g., sales and earnings volatility). A high score means a company has a high-risk label compared to other companies. Our research has shown that across several distinct markets (including our own, the US, UK, East-Asian, and Australian markets), the low-vol signal contains no consistent return predictive information over time. This means that more stable companies do not outperform their more volatile companies over time, and vice-versa. What is interesting, though, is that the signal shows very strong predictability of volatility itself – meaning the companies with historically high volatility tend to experience higher realised volatility in future.

This means that using the signal to pick a set of companies to invest in simply does not work – picking only stable companies means investors would very likely experience less risk, but also earn less reward. There’s no free lunch here. But how can we use this signal better?

The Low-Volatility Recipe

In designing a low volatility index, we aimed to harness the strong predictive power of the low volatility signal in predicting future volatility, but not through the traditional means of exclusion.[1] Instead, we use it as a means of tilting (or marginally increasing exposure) towards more stable companies while preserving the inherent structure of the benchmark index. The aim is to share consistently in the market’s upside while limiting the downside by holding proportionally more stable shares. Tilting is, therefore, the key (managing risk), not sub-setting (avoiding risk altogether) – and this makes all the difference.

In designing the low volatility index, we manage portfolio active risk compared to the FTSE/JSE Capped SWIX to be 4%, making it an investable core alternative to the benchmark index. Other controls are also in place to manage single share- and sector risk concentration, turnover, and other portfolio efficiencies. Ultimately, this means the low volatility index is not designed to be the lowest risk equity strategy available but rather to have a similar, albeit lower risk profile than the representative benchmark (Capped SWIX) through time.

The result of this portfolio construction methodology is interesting, and comparable to other global indices that we tested (including the S&P 500, the FTSE 100, German DAX, ASX 200 and the KOSPI indices). When tilting towards lower volatility shares in a risk-controlled manner, both realised volatility and rolling three-year drawdowns are significantly and consistently improved (by around 2% annualised on average).

Importantly, this lower volatility is not achieved by paying away upside. On the contrary, upside beta is largely preserved. And this is the key, as investors compound more over time, not necessarily by finding alpha, but instead by more effectively and consistently avoiding losses. Lowering exposure to higher risk companies in the index (while not excluding them) provides exposure to their upside, while sharing less in their downside.[2] Alpha through effective risk management is less sexy but can be equally as powerful when done right.

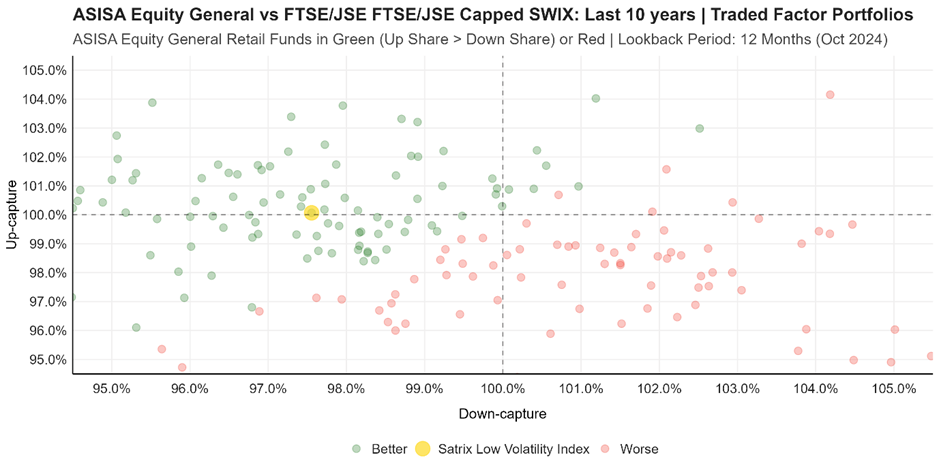

To illustrate the impact of this principle more clearly, we created the following graph that illustrates the “upside vs downside” capture of active local equity managers in the ASISA SA Equity General Category over the past 10 years. For each active manager at each month, we calculate the 12-month upside- vs-downside capture compared to the FTSE/JSE Capped SWIX. Ideally, managers share more in market upside than downside – which is illustrated by colouring such managers green (red implies managers below the 45-degree line, meaning they share proportionally more in downside than upside).

The yellow bubble in the graph shows the Satrix Low Volatility Index. Its ability to preserve beta over this period while sharing significantly less in the downside (below 98% down-capture), is what makes its investment case clear.

Source: Satrix. Data: Morningstar and FTSE/JSE. A methodologically consistent back-test is applied to the Satrix Low Volatility Index. For active managers considered, we strip out fund-of-funds and index tracker unit trusts and control for survivorship bias. We deducted conservative annual Total Investment Charges of 30bps from the FTSE/JSE Capped SWIX Index and 60bps from the Satrix Low-Volatility Index.

The net impact of improved downside risk management is that investors can expect a smoother return profile with less downside while having index-like returns otherwise. Over time, investors can expect to earn more simply by losing less – a powerful investment building block to supplement alpha-seeking strategies.

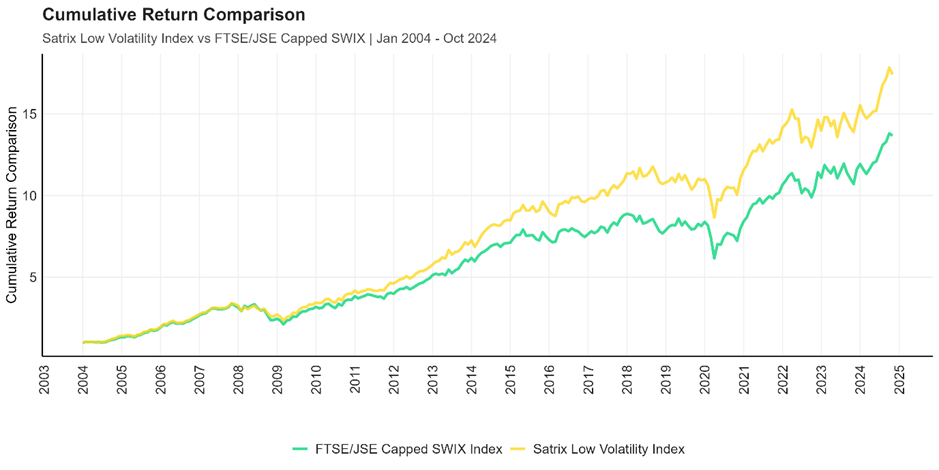

The below graph shows the methodologically consistent back test with a consistent low volatility tilt applied with active risk management compared to the FTSE/JSE Capped SWIX as discussed above.

Source: Satrix. Data: Morningstar and FTSE/JSE. A methodologically consistent back-test is applied to the Satrix Low Volatility Index. We deducted conservative annual Total Investment Charges of 30bps from the FTSE/JSE Capped SWIX Index and 60bps from the Satrix Low-Volatility Index.

Not only do we see lower drawdowns over this 20-year period (lower 78% of the time), but the index also experienced significantly lower realised volatility (just over ~2% less, annualised, on a rolling three-year basis), meaning it had a smoother return profile. It seems that, by systematically reducing (not fully avoiding) higher risk shares, one might after all have one’s cake and eat it.

This article was first published here.

*Satrix is a division of Sanlam Investment Management

Disclaimer Satrix Investments (Pty) Ltd is an approved financial service provider in terms of the Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act, No 37 of 2002 (“FAIS”). The information above does not constitute financial advice in terms of FAIS. Consult your financial adviser before making an investment decision. While every effort has been made to ensure the reasonableness and accuracy of the information contained in this document (“the information”), the FSP, its shareholders, subsidiaries, clients, agents, officers and employees do not make any representations or warranties regarding the accuracy or suitability of the information and shall not be held responsible and disclaim all liability for any loss, liability and damage whatsoever suffered as a result of or which may be attributable, directly or indirectly, to any use of or reliance upon the information. Satrix Managers (RF) (Pty) Ltd (Satrix) is a registered and approved Manager in Collective Investment Schemes in Securities and an authorised financial services provider in terms of the FAIS. Collective investment schemes are generally medium- to long-term investments. With Unit Trusts and ETFs, the investor essentially owns a “proportionate share” (in proportion to the participatory interest held in the fund) of the underlying investments held by the fund. With Unit Trusts, the investor holds participatory units issued by the fund while in the case of an ETF, the participatory interest, while issued by the fund, comprises a listed security traded on the stock exchange. ETFs are index tracking funds, registered as a Collective Investment and can be traded by any stockbroker on the stock exchange or via Investment Plans and online trading platforms. ETFs may incur additional costs due to being listed on the JSE. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance and the value of investments / units may go up or down. A schedule of fees and charges, and maximum commissions are available on the Minimum Disclosure Document or upon request from the Manager. Collective investments are traded at ruling prices and can engage in borrowing and scrip lending. Should the respective portfolio engage in scrip lending, the utility percentage and related counterparties can be viewed on the ETF Minimum Disclosure Document. For more information, visit https://satrix.co.za/products

[1] Typically, low volatility strategies use a subsetting approach – whereby a selection of companies with the lowest volatility scores are picked. E.g. local strategies have considered the 20 least volatile companies out of a selection of mid- and large caps, which is in line with global index design methodologies too.

[2] This makes sense arithmetically, as the nonlinearity of returns imply a positive 10% return followed by a 10% loss does not equate to parity – instead it is a 1% loss from the initial position. The bigger the loss, the bigger the net impact.