By Nico Katzke, Satrix

Investors have been well primed on the benefits of compound returns. What is underappreciated, though, is that not all compounding is equal. In this article we discuss two key pillars of compounding that is understated in importance, but critical to make it work in your favour.

First, the source of compounding determines the rate of compounding. We all know that to earn the proverbial biscuit, you have to risk it. Casinos take a calculated risk with each spin of the Roulette wheel. Many spins make uncertain outcomes near certain. Similarly, diversified exposure to risk assets in financial markets, given enough time, has shown to pay off with high consistency – and at a superior compounding rate.

Second, know your enemy. The anti-matter to compounded returns is compounded costs. A sure way to reduce the exponential benefits of compounding is to tolerate a counter-compounding effect through high fees, costs, and inefficient re-allocations. The sheer impact might surprise you.

First Pillar: Source of Compounding

To understand why the source of compounding matters so greatly, we need to first understand the difference between Saving and Investing.

- Saving means spending less than you earn – storing seeds safely to be consumed later.

- Investing means sowing those seeds for greater harvests in the future.

We need both – but only investing truly benefits from compounding.

Why is that? The evergreen adage of higher risk, higher reward gives us a clue. Risk’s reward crucially relies on differences in our perception and temporal tolerance of it. Savers and short-term investors have less appetite for risking the seeds they intend consuming tomorrow. They thus pay a premium to investors willing and able to bear the possible short-term pain of sowing seeds for the long-term gain they seek. Harvesting risk premiums to truly compound one’s efforts requires time, not timing.

But how much does taking some risk truly matter? The answer may surprise you. To show just how important harnessing the right source of compounding is, we use a simple illustration.

Suppose you have two individuals, Saver and Investor. Both studied the same degree and started earning the same salary 20 years ago. Saver worked long hours and occasionally weekends. Saver is all work, no play. And it shows. Saver earns a whopping 12% salary increase every year.

Investor likes to pursue other hobbies, has a great work/life balance, and works far shorter hours. And it shows. Investor earns a basic 6% salary increase each year in line with inflation.

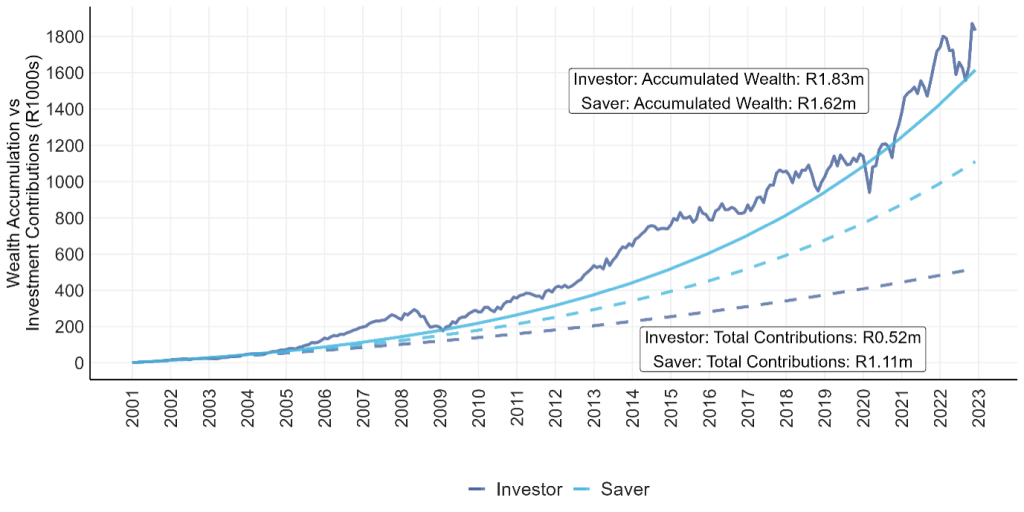

Both have one thing in common – they diligently set aside 10% of their income. What they do with their saving contributions differ though. Saver dislikes risk & prefers certainty and earns a fixed 5% annualised return on a savings deposit account. Investor embraces risk and earns the equity market risk-premium over time by investing in the Satrix Top 40 ETF. Suppose we left them to work 22 years and then reviewed their wealth in 2023. Note the below:

Source & Calculation: Satrix. December 2000 – December 2022.

At the end of 22 years, the hard-working Saver had a final salary more than 3 times that of Investor. He contributed R1.1m to his savings pool (dotted light blue line) and reached an accumulated R1.62m capital (solid light blue line, earning 45.9% on total contributions). Investor put aside half this amount (dark blue dotted line) yet grew her total capital by more than 15% that of Saver (netting a return on total contributions of 252%).

By setting aside capital every month, both enjoyed the benefits of compounding. One just did so significantly more than the other. Saver focused on growing income; Investor focused on what she did with hers. And this made a very big difference. It turns out that being intentional about what you do with your earnings matter far more than simply working to grow it. Very few apply this principle in life though; we are mostly conditioned to become income maximisers, not wealth creators.

The lesson is clear, but some might not be convinced. In fact, many would argue that “this time is different”, or TTID. Considering all the turmoil, currency uncertainty and all that, earning equity market risk premiums today might seem too risky and so choosing safer, less rewarded alternatives seem prudent. But if history has taught us anything, it is that TTID is only right in the short-term and can be the enemy of long-term wealth creation.

Consider that if we were to randomly select a day in the past and invest R1 in the All-Share index since 1995 – the odds of returning more than 5% annualised are 74%, 82% and 93.9% respectively over 1, 3 and 5 years (this is in line with other global equity indexes too). Similar to the casino relying on multiple spins of the wheel to make uncertain outcomes near certain – time & patience places the odds firmly in your favour to earn the equity premium.

Second Pillar: Know Your Enemy

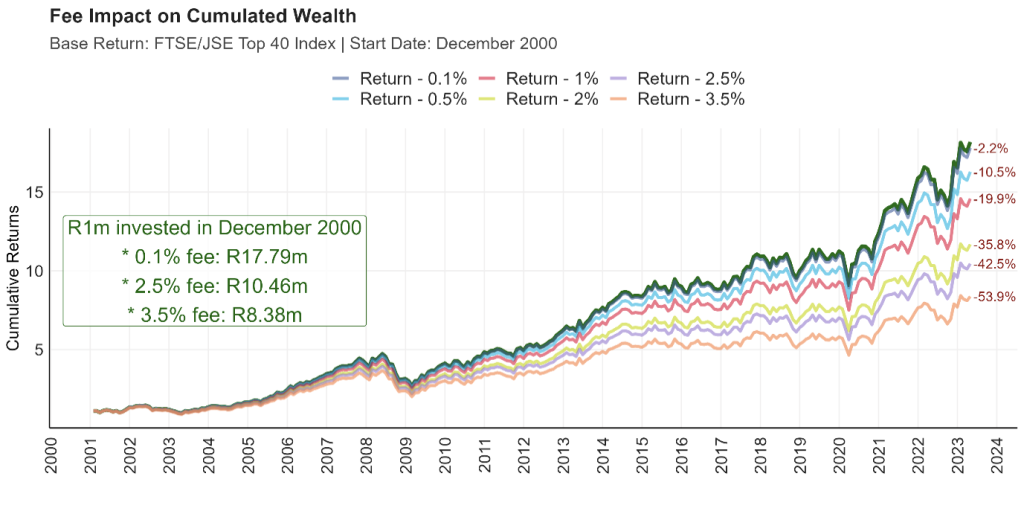

The second pillar to making compounding work for you is avoiding its archenemy: costs. If we were to take Investor’s success above and apply a cost layer to it – her nest egg fast erodes. As before, the scale is more surprising than the statement: R1m invested in the Top 40 since 2000 would’ve been worth less than half if it had an annualized fee of 3.5%. The compounding impact of fees is crystal clear when you see it. Below we show different fee scales and show at the end how much total return were lost accordingly.

Source: FTSE/JSE. Calculation: Satrix. December 2000 – April 2023.

Conclusion

We often hear that compounding is the 8th wonder of the world and that it is a powerful force for wealth creation. In this short piece we argue that to truly harness the wealth creating potential of compounding, we need to know what the source is of compounding, and also, what is working against it.

Compounding works best if you harvest well-diversified and fairly rewarded risk premiums (such as those earned in equity markets) while limiting investment costs. Only then will this wonder truly work its magic in your portfolio.

Disclosure

Satrix Investments (Pty) Ltd is an approved FSP in term of the Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS). The information does not constitute advice as contemplated in FAIS. Use or rely on this information at your own risk. Consult your Financial Adviser before making an investment decision.

While every effort has been made to ensure the reasonableness and accuracy of the information contained in this document (“the information”), the FSP’s, its shareholders, subsidiaries, clients, agents, officers and employees do not make any representations or warranties regarding the accuracy or suitability of the information and shall not be held responsible and disclaims all liability for any loss, liability and damage whatsoever suffered as a result of or which may be attributable, directly or indirectly, to any use of or reliance upon the information.

lovely and insightful piece. Thanks

well, no, timing can be important, if lazy but risk taking investor got retrenched in 2020 during covid, she would have had much less than diligent saver.

what is the difference between R1,83 million and R1,62 million? a mere R220 000. the difference is greed. But at least saver had peace of mind and contentment, while investor had to worry about the vagaries and fickleness of the markets. The only strong point of the article is the one about fees.

Strongly disagree with your sentiment: the greatest risk in the long-term is not taking any risk.

Your point on retrenchment in 2020 is not valid – you need to look at the difference between the dotted line and the solid line (i.e. returns on contributions). Investor contributed far less to his investment pool yet earned far more – even if retrenched in 2020, her return on contributions far exceeded Saver’s and she would’ve been far better covered. Your point on a mere R220k difference ignores that Saver contributed more than double what Investor did, yet Investor still earned much more (a return difference of 252% vs 45%).

Taking too little risk over the long-term when setting aside contributions only provides comfort to those that are ignorant of the very real erosion power of inflation – which deposit instruments do not really shield you from.

Being productive with your capital requires taking some risk (sowing seeds, not just storing it) – and if you have the ability to take a longer-term view, being unproductive with capital (i.e. overly risk averse) is the truer risk. This has nothing to do with greed – it is purely a sensible risk / return calculation.

Great article Nico!

On the topic of fees, it might be worth doing an analysis on the average fee financial advisers charge on the capital they manage and how much active funds need to outperform the benchmark in order for investors to actually earn alpha returns above the market (break-even point). I’m still a young investor (23 years old) and would love to see whether financial advisers bring alpha to the table when selecting active, discretionary fund managers. Naturally, financial advisers have expertise when it comes to other services such as estate planning but as it pertains to investing hard-earned savings, is it truly efficient having a double layer of fees being charged on your investments?

I can see both Monk’s and Nico’s points. I guess Monk means that the investor was saving less and spending more money while earning better returns than Saver who supposedly had less fun and lived frugally, oblivious/satisfied to/with the inferior returns on his capital allocated.

When things go south like in 2020 and Monk’s scenario of retrenchment transpires then Investor has less money to rely on. And, if Saver was unfortunate to also be retrenched, he might have better employment prospects compared to Investor after working hard and getting much better raises. All Investor would have more of during unemployment are fond memories of hobbies once enjoyed now that money has dried up for that. All very hypothetical.

Let’s also remember that an important principle for financial planning is to have a STRONG emergency fund to tide over unforeseen circumstances so that you don’t have to dip into investments when times are tough.