Until fairly recently, investing in China via Naspers as a proxy for the underlying Tencent business was very profitable for South African investors. However, the Naspers share price has more than halved in the past 15 months in line with the falling value of Tencent (I won’t get into the byzantine debate about whether Naspers or Prosus is the greater or lesser of two evils). Now many people are wondering whether or not it is worth getting back into Tencent or Chinese tech stocks generally.

That question is probably best answered by acknowledging that the best returns from these stocks are probably over and although they may have some interesting trading opportunities ahead, the old adage of caveat emptor strictly applies to investment in China generally. It is not for the faint-hearted.

Many years ago, a captain of South African industry told me that if I could spot paradigm shifts taking place before they became common knowledge, then as an investment analyst I would steal a march on my competition. That was very sage advice and remains as relevant today as it was in the 1980s and 1990s. Arguably the largest paradigm shift in the global economy these past thirty years has been the inexorable rise of China from being a relatively insignificant, though vocal society under Mao Zhedong into the world’s second largest economy.

Conventional wisdom tells us that China will soon overtake the US as the leading global economy and that the world will shift from being a unipolar economy, dominated by the US to being something more akin to a bipolar or even multipolar situation with China being at the top of the pile. But that view of the world has been shaken to the core with the impact of the Sars-CoV-2 pandemic and the rapid de-globalization that has set in during the past three years. In this article, we examine how China may evolve in a low growth, de-globalized economy and where the Chinese population is actually declining for the first time in a generation.

Ever since the early 1990s. China has been seen as the great land of investment opportunity. Its strong, sustained economic growth initiated by Deng Xaio-Ping in 1979 has been hailed by many observers as nothing short of miraculous. The country has been transformed from a largely agrarian society into a modern, relatively developed state. And during this time, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has managed to hold onto power, with its rather unique brand of state capitalism, that allows a degree of free enterprise to co-exist. But global and local dynamics are changing rapidly and the conditions that helped create the world’s second-largest economy are disappearing rapidly.

The CCP knows this and is desperately trying to keep the Chinese economy moving at a rapid pace, but the odds are definitely against it. The combination of de-population and de-globalization coupled with the fact that the Chinese economy is maturing means that we should not expect to see Chinese GDP growth of much more than 2% to 3% on average in future.

The Lewis Turning Point

Much of China’s strong economic growth in the 1980s, 1990s and into the first few years of the new millennium was predicated upon the vast movement of people from the rural to urban areas. In a seminal working paper for the IMF in January 2013, authors Mitali Das and Papa N’Diaye postulated that China would reach the Lewis Turning Point and from there would experience a precipitous decline in GDP growth.

The following extract is from the executive summary:

“China’s large pool of surplus rural labour has played a key role in maintaining low inflation and supporting China’s extensive growth model. In many ways, China’s economic development echoes Sir Arthur Lewis’ model, which argues that in an economy with excess labour in a low productivity sector (agriculture in China’s case), wage increases in the industrial sector are limited by wages in agriculture, as labour moves from the farms to industry (Lewis, 1954). Productivity gains in the industrial sector, achieved through more investment, raise employment in the industrial sector and the overall economy. Productivity running ahead of wages in the industrial sector makes the industrial sector more profitable than if the economy was at full employment and promotes higher investment. As agriculture surplus labour is exhausted, industrial wages rise faster, industrial profits are squeezed, and investment falls. At that point, the economy is said to have crossed the Lewis Turning Point (LTP).”

Average wages in China have risen by around 12 times since 2000 but labour productivity has only risen by a factor of 2 to 3 times, suggesting that China has reached the LTP. The LTP is a well-known and documented economic phenomenon and has occurred in most developed countries at some point in time. In China’s specific case, it has been badly exacerbated by the impact on population of the disastrous one-child policy, also introduced by Deng in 1979.

De-population

The one-child policy persisted from 1979 until 2016, during which time it was ruthlessly prosecuted, especially in the urban areas. The CCP finally woke up in 2016 when the one-child policy was revised to allow two children and then again in May 2021 to the current situation that permits three children. But the damage has been done. Chinese couples are no longer interested in having large families. Their priorities lie elsewhere as they rapidly urbanise.

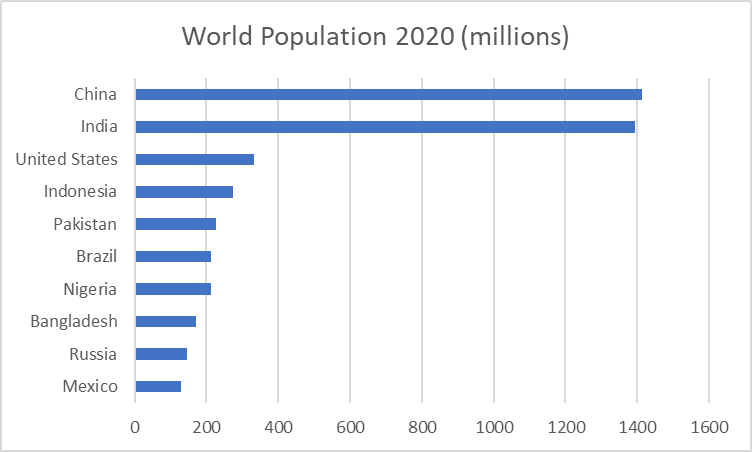

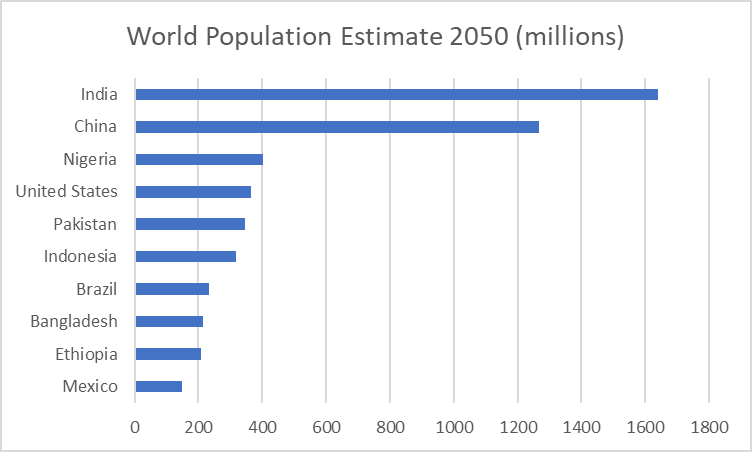

As can be seen from the two charts from the Population Reference Bureau below, China’s population is forecast to fall from just under 1.4 billion people in 2020 to just over 1.2 billion in 30 years’ time. By that time, India will have by far the greatest number of people. And this is probably a very conservative estimate. The Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences predicts an annual average decline of 1.1% after 2021, pushing China’s population down to 587 million in 2100, less than half of what it is today. Controversial billionaire Elon Musk recently tweeted that he believes China will lose around 40% of its population in a generation if present birth rates continue.

It is therefore no exaggeration to say that China has the world’s worst demographics.

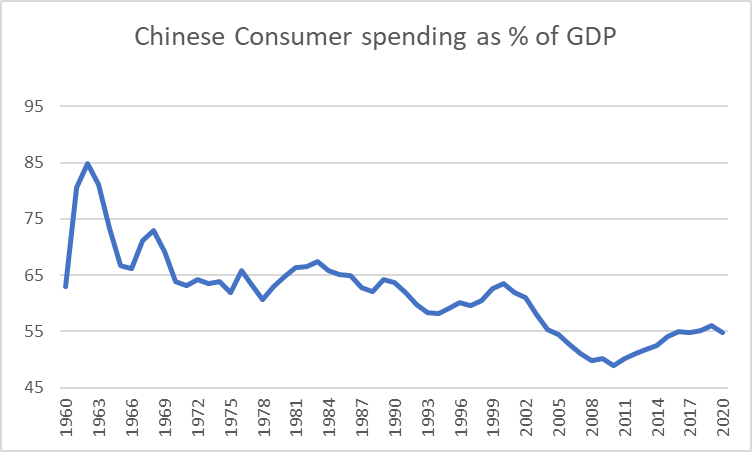

Normally this wouldn’t be a train smash as in most developed countries, the trend is a move away from heavy manufacturing and into services, with the emphasis being on consumer-related activities. But in China this is a problem, as China’s consumption to GDP ratio is probably the lowest of any large economy in the world. The reasons are many and varied but right near the top is a very high savings ratio due to huge uncertainty surrounding pensions, healthcare and education costs. So this cohort has had to put precautionary money aside over many decades just to feel secure in old age. In other words, they have deferred consumption in favour of personal welfare spending. And until the CCP takes concrete steps to greatly improve social welfare programmes, this phenomenon will likely persist.

The following graph shows that Chinese consumer spending as a percentage of GDP has been in secular decline since 1962 and shows no signs of reversing direction.

De-globalisation

Globalisation – that process by which the world became increasingly interconnected due to greatly increased trade and cultural exchange – is under threat and soon may no longer exist as we currently understand the term. On balance, globalisation has been a force for good over many years and has helped over a billion people pull themselves out of poverty. Additionally, improved trade and information links with the growing middle classes in autocracies such as China and Russia have sustained the cause of liberalism, thanks mainly to globalisation.

If globalisation were to retreat into something more akin to what we endured during the Cold War period between 1945 and 1990, it would indeed be tragic. But unless the free world starts changing its attitudes to autocracies intelligently, that could be the outcome in a few years’ time.

Globalisation has been happening for hundreds of years, but has quickened dramatically in the last half-century, notably with the extermination of communism in eastern Europe and the USSR from the late 1980s and the Chinese economic miracle since the late 1970s. The most noticeable impacts have been in the areas of greatly enhanced international trade, the emergence of a plethora of true multinational companies, freer movement of capital, goods, services & people (as in the case of the European Union), a greater dependence of the global economy in terms of outsourcing and insourcing and recognition of companies such as Amazon, Facebook, Twitter, McDonald’s, Google and others in less economically-developed countries.

Globalization’s heyday was 30 years from the mid-1980s onwards, when outsourcing of manufacturing to less developed countries in far east Asia, especially China, really took off. But that is now evaporating and the trend has been exacerbated by the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, as progressively more and more developed countries begin on-shoring and moving away from these formerly low-cost manufacturing jurisdictions.

The impact of globalization on China is nicely encapsulated by the Chinese journalist Ma Jun who said:

“Globalisation has powered economic growth in developing countries such as China. Global logistics, low domestic production costs, and strong consumer demand have let the country develop strong export-based manufacturing, making the country the workshop of the world.”

The Cult of the Personality

The most successful era of Chinese economic growth has been under collective leadership. But the current leader, Xi Jinping wants to consolidate power under his authority alone and to that end is seeking a third term in office at the 20th CCP Congress in October this year. Xi wants his legacy to rival that of Mao Zhedong, the founder of the People’s Republic of China. And while Mao’s reign, if viewed dispassionately, was hardly a roaring economic success, Mao is still held in extremely high regard. Xi knows this and is keen to preserve a legacy that matches Mao’s, regardless of the economic realities.

Under Xi’s leadership, China has effectively been under stop/start lockdowns in various parts of the country for over two years. It has adopted a slavish adherence to a so-called “Zero-Covid” policy that common sense dictates cannot be won. In the early stages of the pandemic, Chinese vaccines were relatively effective against the original Wuhan strain of the virus but against Delta and especially Omicron, they are largely useless. So the CCP has resorted to ordering massive lockdowns of entire cities such as Shanghai to attempt to eliminate the virus, to little or now avail.

Meanwhile, Chinese industry is suffering, as Chinese supply chains take the strain as more and more countries start on-shoring away from China. The solution to this problem is glaringly obvious to anyone not blinded by political dogma: import the required western vaccines (probably mRNA ones from Pfizer or Moderna). That would be regarded as failure on the part of the Chinese state. Xi is personally identified with the Zero-Covid policy and any criticism of the policy is seen as criticism of him and that is not acceptable in the totalitarian Chinese state.

Another area where Xi has fallen is in his so-called “Common Prosperity” and “Dual Circulation” visions, which have mainly arisen since the start of the US trade wars. In a nutshell, these policies aim to tackle inequality, monopolies and debt and to turn China into a type of fortress against any further possible trade tariffs or sanctions. All of these will be dictated from a central government level, with all the accompanying bureaucracy and red tape.

Until very recently, China had a flourishing tech sector that was about to overtake that of the acknowledged leader, Silicon Valley in the US. But Xi has changed all that with his ruthless crackdowns on this sector, using all sorts of flimsy excuses for clipping its wings. In a re-worked state capitalist system with a demagogue at the helm, there can be only one voice and that voice is Xi’s.

And then to top it off, Xi wants to increase the role of state-owned enterprises in the economy and use more debt to expand its already large footprint. Bottom line is that under Xi’s envisaged third term in office, he will ensure that ideology trumps good business sense. Meanwhile investors have voted with their feet. The CSI 300, a broad measure of stocks listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, is deep in bear territory, having fallen some 28% from its February 2021 peak. This is substantially worse than the Nasdaq or S&P 500 and the decline set in much sooner.

Investors may be making a gradual return to China but it is likely to be a slow process and it still remains unclear how much autonomy, if any, will be available to Chinese tech companies when it comes to running their businesses. What is clear is that there is an inexorable move to the left in Chinese politics and a much greater role for the state in future. But, that in itself doesn’t necessarily make China un-investable.

However, what it does mean is that investors should not expect that same degree of return that they have experienced in the past and that they should also view Chinese investment with a high degree of healthy skepticism.

Taiwan

Following Russia’s disastrous invasion of Ukraine, many observers have begun speculating about the possibility of China doing a similar thing with Ukraine. But there are major obstacles, both physical and financial, that China would need to overcome if it was to be assured of victory in a Taiwan invasion.

The first point to note is that China was probably watching the west’s reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to see if it could pull off a similar exercise against Taiwan and not get heavily sanctioned for it. China must have been incredibly surprised at a) the cohesive sanctions applied by the west against Russia in response and b) the degree to which the Russian military failed to gain a decisive victory in Ukraine.

Taiwan is altogether different to Ukraine from many angles.

Firstly, while Ukraine has only been preparing for war since 2014, Taiwan has effectively been on a war footing with China since 1949. Secondly, while Russia was able to literally drive its tanks and heavy weaponry straight into Ukraine, a Chinese invasion of Taiwan would be considerably more difficult from a logistical perspective. And then finally, an armed invasion of Taiwan by China would be met by stiff sanctions from the west, if the Russia/Ukraine conflict is anything to go by.

While most countries respect China’s One-China policy with regards to Taiwan, they would expect a peaceful, negotiated conclusion to this policy and would have no truck with an aggressive invasion of the island. Sanctions against China would likely be far more effective than those currently deployed against Russia. While Russia is self-sufficient in fuel and food, China is certainly not and has to import around 85% of its food requirements. Energy, too, is largely imported.

So, China could be crippled quite quickly in the event of comprehensive sanctions being applied. China also desperately needs to be part of the global community, regardless of Xi’s efforts at Dual Circulation. If access to the outside world were cut off, China’s balance of payments would deteriorate rapidly.

For more analysis and insights from Chris Gilmour, follow him on Twitter.

A very interesting and enlightening article for a lay person in that field, Chris! Thank you very much. I was just wondering whether our government was taking after China with that autocratic type of economic policy? With the high import of Chinese goods (of not always good quality) on the market the relations of SA with China must most probably be strong.

A most insightful article. Chris’ views on Naspers and Prosus are disturbing. Investors will hope he is wrong in his estimation of the future trajectory of these companies.

A couple of observations: –

1. On demograhic decline: – 1-2% GDP growth combined with 1.1% annual population decline implies GDP Per capita growth of 2-3% not all that bad if you a citizen, not so good if you building infrastructure….

2. On International Sanctions – China has become the #1 trading partner for many, many countries around the world, especially in SE Asia, and Africa… Don’t over estimate the influence of the US on these countries. They may prefer doing business with the US but China pays the bills. Any comprehensive sanctions on China will have catestrophic affects on the world economy not just on China = > An invasion of Taiwan is a doomsday scenario.

3. – US has its own problems – Don’t assume anthing like a return to leadership by the US.. Their political system is completely disfunctional, and their fiscal position is precarious, and will only return to normal through the debasement of their currency which only enhance the downward trajectory of their politcal influence..

Interesting times indeed… and whilst I wish I could share you optimism about the relative strengths of the US (And the west) versus China… I remain sceptical.

A very interesting point of view but can’t agree with his conclusions. China has spent billions opening Asian markets to keep growth at higher rates

I

Agreed a Taiwanese invasion is a doomsday scenario. Hopefully it will never comes to that. The one thing I didn’t mention is China’s utterly horrific debt levels. Frankly they are off the scale and it doesn’t matter where they are concentrated..in munis for example. That debt has to be repaid. As interest rates rise it becomes progressively more difficult to do so.

China NEEDS globalization more than any other large economy. You are right in the sense that it has pushed a lot of manufacturing the way of surrogate E Asian countries such as Vietnam, Laos, Bangladesh etc. but as globalization fizzles out, which it is already doing, they all suffer. Eventually many of these sweat shop countries incl China will be marginalised by technology such as 3D printing and additive manufacturing. But in the meantime, China needs to keep the west sweet in terms of buying its products.