If art is a mirror, as the saying goes, then the Venice Biennale offers what can only be described as a panoramic reflection of the world in 2024. In this exclusive for Ghost Mail, Dominique Olivier takes you on a journey into how contemporary art is the outlet for humanity.

Say what you will about contemporary art, but you can’t argue the fact that it delivers a message like very few other things. Every two years, the Venice Biennale stands in as a kind of megaphone to amplify the voices of artists from almost every country in the world. Official statistics reveal that in 2022, more than 800,000 visitors attended this global art exhibition, which runs from April to November.

That’s a lot of people, looking at a lot of art. And this year, I was lucky enough to count myself among them to bring Ghost Mail readers an experiential look at this incredible event.

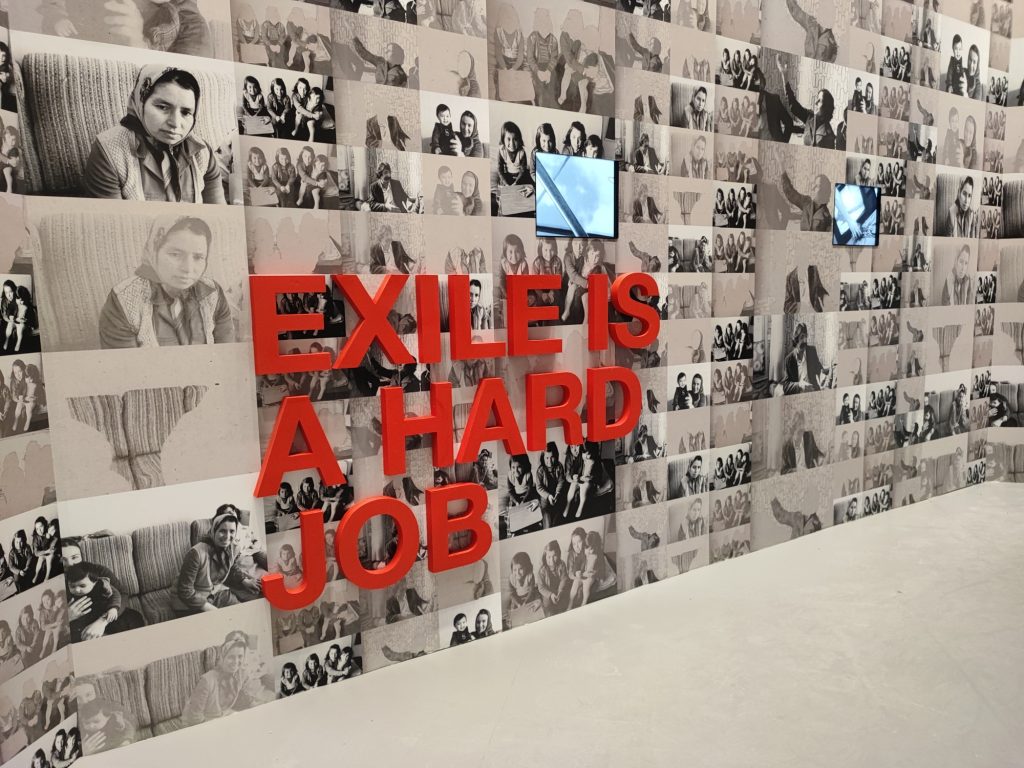

This year’s theme, “Foreigners Everywhere”, introduced works and conversations centred around immigration, refugees, exile, outsiders and those who live on the margins. It’s an evocative theme, made all the more relevant and powerful as hostilities between countries continue to play out in the background of the event.

The politics of space

It’s an awkward thing to have to represent your country on the international stage while you’re in the throes of war. Russia and Israel each have a private pavilion in the sought-after Giardini section of the Biennale, while Ukraine has a space in the shared Arsenale space a short walk away.

Before you wonder if there is some sort of favouritism in the allocation of pavilions – there genuinely isn’t. The Giardini (literally, “garden”) is the original site of the Biennale, which in its earliest days was confined to one building. As more countries were invited to participate over time, space became a problem in the main building. Biennale organisers started encouraging countries to invest in and build their own pavilions in the Giardini, with Belgium being the first to do so in 1907. Since then, 28 other countries have built pavilions, with Korea claiming the final spot in the Giardini in 1995.

The Giardini reached capacity at the end of the 90s. Countries not owning a pavilion started exhibiting in other venues across Venice, with the majority renting exhibition spaces in the restored Arsenale (the largest production centre in Venice during the pre-industrial era, responsible for churning out those famous Venetian galleons).

Russia built its pavilion in 1914, while Israel built theirs in 1952. Ukraine made its first appearance in the Arsenale in 2003, about eight years too late to claim a spot in the Giardini.

You’re probably wondering how our local artists make do at the Biennale. After being ostracised for decades due to the Apartheid regime, the South African pavilion had its debut in the Arsenale in 1993. It’s not the Giardini, but it’s a decent space.

I know I said there isn’t any favouritism that plays into the allocation of exhibition spaces, and that is mostly true. Still, we can’t really ignore the fact that the countries represented in the Giardini are the ones who were able to afford to build a pavilion between 1907 and 1995 – a period of time that saw both World Wars and the Cold War come and go, along with loads of other global events.

This means that an overview of the Giardini versus the Arsenale gives you quite a good idea of who the developed market players in the world are, compared to those who have traditionally existed on the fringes. In the Giardini, you’ll find Great Britain, North America, Germany, France, Switzerland and Japan. In the Arsenale, you’ll find China, Indonesia, Mexico, Singapore and the UAE.

Emerging vs. developed markets, anyone?

Russia/Bolivia

While each exhibition space at the Biennale is representative of a country, having an artist from that country exhibiting there is more of a convention than a rule. Historically, some countries have invited artists from other nations to exhibit in their spaces for various reasons.

A good example would be the tiny island nation of Tuvalu, an island country in Polynesia that very few people ever expected to see represented at the Biennale due to the costs involved in exhibiting. Tuvalu is forecast to be one of the first countries in the world to disappear due to rising sea levels brought on by global warming. Desperate to bring attention to their plight on the global stage, Tuvalu came to the Biennale in 2013 and 2015. In both instances, they selected globally-renowned Taiwanese eco artist Vincent J.F. Huang to represent them and their message.

I was morbidly curious to see what would be going on in the Russian pavilion this year. I was very surprised to encounter a kind of pop-up pavilion for Bolivia inside the Russian building. This is not the same as Vincent Huang representing Tuvalu; the Bolivians are representing themselves, not Russia.

The official story is that Russia is “lending” their space to the Bolivians this year. Russia itself hasn’t been represented at the Biennale since the country first invaded Ukraine in 2022. Their 2022 exhibition was cancelled on February 27 of that year, just days after the first invasive action. Artists Alexandra Sukhareva and Kirill Savchenkov, as well as curator Raimundas Malašauskas, announced their resignation on social media. “There is nothing left to say, there is no place for art when civilians are dying under the fire of missiles,” wrote Savchenkov. “As a Russian-born, I won’t be presenting my work in Venice.”

It may seem like a random alliance – Russia and Bolivia – but the decision coincides with cultural cooperation, lithium extraction and atomic research agreements between the two countries. In 2023, Bolivia signed a lithium agreement with Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear agency, on tapping the country’s reserves of the metal. Bolivian president Luis Arce openly congratulated Vladimir Putin for his victory with over 87% of the vote in the 15-17 March presidential elections.

Art. Politics. It’s all connected.

Israel

Not far from the Russian/Bolivian pavilion, the Israeli pavilion stands in darkness. Israeli artist Ruth Patir, who was chosen to represent Israel at the 2024 Venice Biennale, announced she will not open her exhibition for the national pavilion until “a ceasefire and hostage release agreement” is reached between Israel and Hamas. Patir, along with the pavilion’s curators, Tamar Margalit and Mira Lapidot, did not inform the Israeli government ahead of time about their decision to postpone the opening. The pavilion, titled “(M)otherland,” was set to include several new works featuring computer-generated imagery; one piece remained partially visible through the front window during my visit.

In mid-October last year, a few weeks into the Gaza conflict, Israel confirmed its intention to move forward with the pavilion, despite calls from the art world for the country to withdraw. In February, thousands of artists signed an open letter urging the Biennale to cancel Israel’s participation, accusing the event of “platforming a genocidal apartheid state.” Several artists in the main exhibition joined this call. Italian Culture Minister Gennaro Sangiuliano responded by confirming that Israel would participate as planned, emphasising that any country officially recognised by Italy is entitled to present a national pavilion. Come for the art, stay for the pizza.

Curator Francesco Bonami’s proposal to include a Palestinian pavilion at this year’s Biennale was immediately met with claims of antisemitism, and the country ultimately did not mount a presentation. To date, Palestine has never been represented at the Biennale.

Ukraine

Ukraine was well-represented at this Biennale this year, which is a feat made all the more impressive when you take into account that they also managed to get an exhibition to the Biennale in 2022. La Biennale, the cultural organisation behind the entire event, committed to supporting Ukraine’s national pavilion in 2022, which had to pause preparations following Russia’s invasion. In addition, a temporary “pavilion” called Piazza Ucraina was set up by the Biennale near Russia’s closed pavilion. This last-minute tribute to the embattled country featured a wooden structure that appeared charred, symbolising the devastation Ukraine has faced.

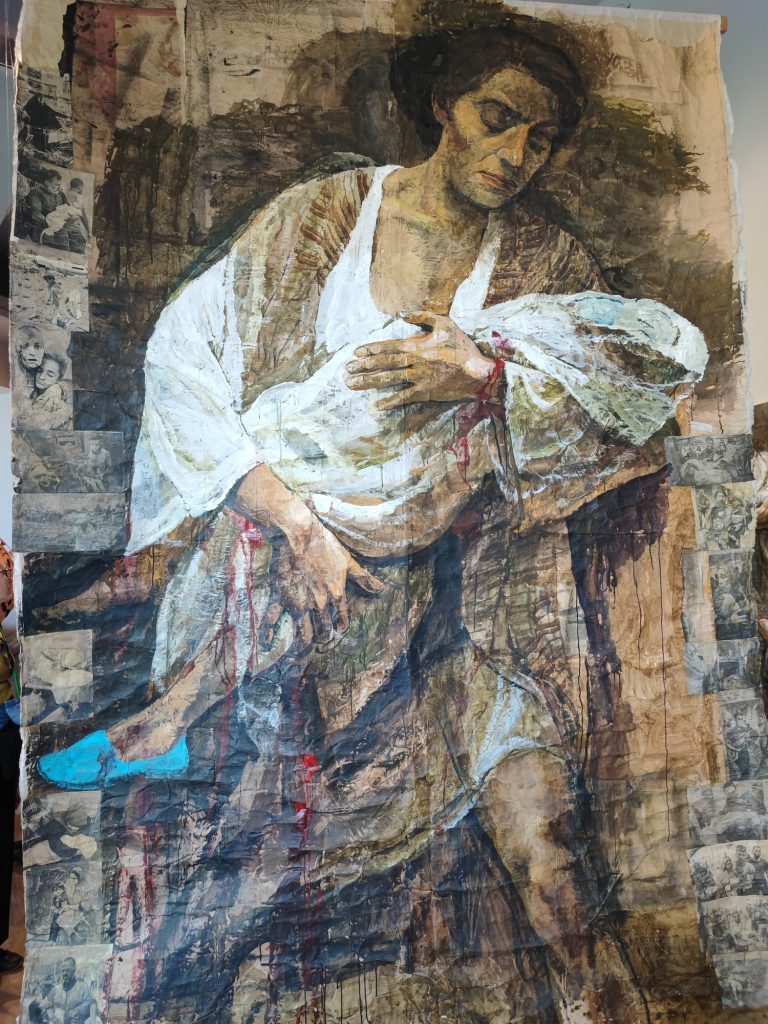

This year’s Ukrainian pavilion in the Arsenale has not left my mind since I saw it. Titled Net Making, the exhibition features the works of various Ukrainian artists, installed in a space that has been swathed in camouflage netting. As per the curator’s statement, “People in Ukraine and abroad, often strangers, gather to weave together camouflage nets. It’s a practice driven by tragedy, but it can also function as therapy or social occasion. It is the epitome of self- organisation, horizontality and joint action, and a means of emancipation”.

All of the works in the space are excellent, but the one that made me feel slightly sick (in a good way) was Civilians. Invasion by Andrii Rachynskyi and Daniil Revkovskyi (yes, there’s a full stop in the middle of the title). This video work features archival videos collected from open sources, shot by civilians before and during the Russian invasion.

In home-video style footage, two small children respond with excitement when their mother returns from the store with a pair of ice-creams for them; she could not finish the shopping, she explains, because there was bombing, so she grabbed the ice-creams and ran. A distressed woman paces in the street, describing to her neighbour that she was walking her dog, who then ran off at the sound of an explosion. A couple searches for their belongings in the bombed-out remnants of their apartment. These glances into the “new normal” are visceral yet magnetic, and I’ll admit that I stood there and continued to watch far past the point of my own comfort.

On the wall across from the screen showing these videos, there’s a first-person shooter video game playing on loop. The space asks you to consider how easy it is to kill people on PlayStation vs. the tragedy in real life.

Biennale 2026

As I dream of returning to Venice in 2026, I can’t help but wonder what the next Biennale might look like. The political, social, and environmental challenges of recent years have set the stage for more urgent conversations in the art world, and 2026 could see a Biennale that continues to push boundaries in these areas. We might expect even deeper explorations of displacement, identity, and global interconnectedness – especially as climate change, geopolitical tensions, and technological advancements continue to shape our world.

Will we see more collaboration between countries, new voices from previously underrepresented regions, or an even bolder critique of power dynamics? Will we see the introduction of an AI pavilion? Only time will tell, but one thing is certain: the Venice Biennale will once again offer a window into the heart of the world, and that is a window worth keeping an eye on.

The gelato certainly isn’t bad, either.

About the author: Dominique Olivier

Dominique Olivier is the founder of human.writer, where she uses her love of storytelling and ideation to help brands solve problems.

She is a weekly columnist in Ghost Mail and collaborates with The Finance Ghost on Ghost Mail Weekender, a Sunday publication designed to help you be more interesting.

Dominique can be reached on LinkedIn here.

A powerful article. One that reminds me again that the world could never exist in a vacuum as even art is impacted by geopolitical happenings.

I really don’t see the point of these articles for increasing one’s financial knowledge

That’s because they are in no way aimed at increasing financial knowledge. There’s a lot more to the world than markets, especially on a Sunday morning as part of Ghost Mail Weekender. If you prefer to stick to just the financial stuff, every single other article on the platform each week is aimed at that. Dominique’s column is about storytelling.

I really enjoy the articles. Interesting and insightful. Thank you, Dominique & Ghost!

I REALLY ENJOY THE ARTICLES, SOMETHING DIFFERENT, AND A DIFFERENT VIEWPOINT