Because if they won’t, then the actions of the Fed are going to cause untold misery around the world. Chris Gilmour takes a closer look at an alternative thesis.

Conventional wisdom at the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) and a few other central banks globally is that the main culprit behind stubbornly high inflation is excessive demand. That being the case, the remedy appears simple: just keep on increasing interest rates until the excess demand gets choked off and everything reverts to normal.

But what if they’re wrong? What if this inflation is NOT necessarily caused by excess demand, but by other factors? Would this mean that we’re going down the wrong path?

Is there another cause?

No less a figure than the Fed’s 2IC, Lael Brainard, has suggested recently that US inflation may be caused not only by the usual suspects (high food and fuel prices) but also by overly-aggressive expansion of profit margins by retailers and other consumer-facing industries, such as auto dealers. She had to steer a cautious path when making these comments, so as not to appear overly anti big business, but the message was clear. Addressing a meeting of the National Association for Business Economics in Chicago, Brainard asserted that “there is ample room for margin recompression to help reduce goods inflation” in the retail economy. In other words, she is asking business to reduce margins to help reduce inflation.

“Retail margins have increased 20% since the onset of the pandemic, roughly double the 9% increase in average hourly earnings by employees in that sector,” she said. “In the auto sector, where the real inventory-to-sales ratio is 20% below its pre-pandemic level, the retail margin for motor vehicles sold at dealerships has increased by more than 180% since February 2020, 10 times the rise in average hourly earnings within that sector.”

So what? What does it matter what is causing the inflation? Surely what matters is how we get rid of it?

No.

The Fed wasted precious time in 2021 debating whether or not inflation caused by a massive expansion of the money supply was going to be more than just temporarily inflationary. In so doing, it let inflation build up a head of steam that only got greater, thanks to higher food prices and then the coup de grace, the war in Ukraine.

But we have to be careful and not fall into the trap of thinking that there is necessarily a quick, easy and indeed an elegant solution to the inflationary spiral in which we find ourselves. And we need to avoid making knee-jerk reactions to try to combat this inflation.

Where did this inflation come from?

Let’s go back to first principles and discover the roots of this great inflation. Until the start of the Covid pandemic, inflation was extremely benign and wasn’t an issue for any country. But in an attempt to combat the worst effects of the pandemic, most governments around the world (both in developed and emerging economies) borrowed to the hilt and expanded their balance sheets significantly. The end result of such an exercise was always going to be inflationary. It manifested itself in the US and the developed world in huge pent-up demand that exploded into an orgy of spending as lockdown restrictions were relaxed.

Fed chair Powell was correct in assuming that this would only be temporary, referring to it as “transitory”.

However, certain other factors – notably those relating to supply-chain disruptions – occurred during lockdown. The manufacture of semiconductors (silicon chips) virtually ceased as car production ground to a halt. This was reflected in a massive deficit of new auto availability as the lockdown restrictions were eased, resulting in the prices of both new and used cars rising almost exponentially.

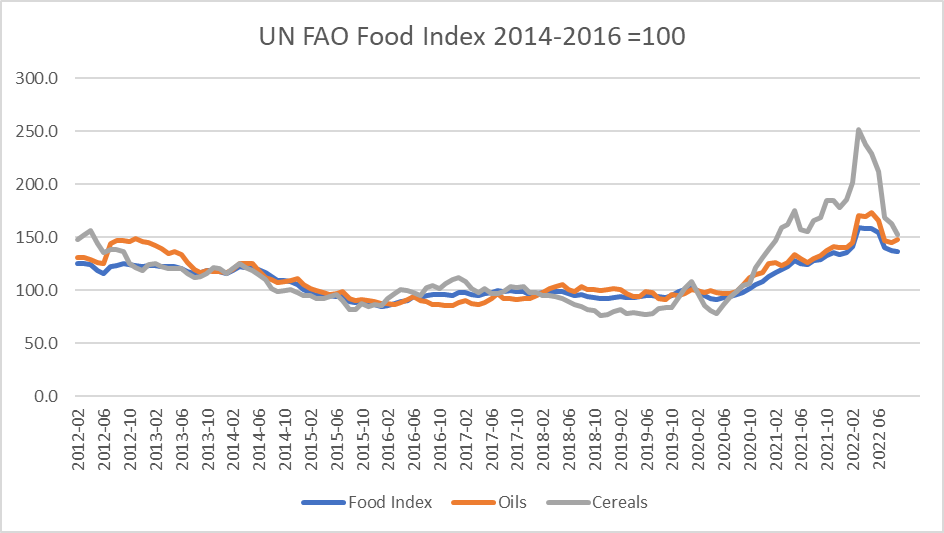

But once again, looking at it rationally, Powell could be forgiven for thinking that this was another transitory inflationary effect. At the same time, food prices (which had been rising before the pandemic struck) rose very rapidly. This was due to a variety of reasons, mainly climate-related. Only in the last few months have food prices started softening, and they are now similar to where they were two years ago.

The oil price exhibited some bizarre behaviour at the onset of the pandemic, going to less than zero on a forward basis for a brief period in time. But then, gradually, it started increasing and when the war broke out in Ukraine, it spiked, along with gas prices, which had been increasing rapidly before then. Since then, of course, it has settled back to roughly where it was before the conflict.

So many of the factors that are associated with causing the great inflation appear to be subsiding, fuel and food being most notable. But that’s only really the case for US consumers, shielded as they are from currency fluctuations, as both food and fuel are denominated in US dollars. Most other countries with few if any exceptions, have seen their currencies depreciate significantly in the face of a resurgent dollar, helped by the Fed increasing US interest rates.

Where will inflation settle?

Inflation is probably going to settle at a higher average level than where it was prior to the coronavirus pandemic. The main reason for this lies in the change in globalisation dynamics (the effective end of globalisation as we have got used to it) and structural changes to supply chain dynamics. The US is bringing back a lot of its manufacturing onshore, after many decades of outsourcing it to far east Asia and specifically to China. For the first few years, this will be structurally inflationary, as the country gears up to get the economies of scale required to produce what is currently being produced offshore. After that, the inflationary forces will subside. But this could take five to ten years to achieve.

So, back to Lael Brainard. If she is correct, then increasing US interest rates much beyond where they currently are will likely achieve very little of a positive nature but will cause untold misery around the world. Many emerging economies were already facing a debt crisis long before the dollar’s upwards surge. Sustained strength in the greenback could well be the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

Global impact

And even in countries such as SA, which has most of its debt denominated in local currency rather than USD, there is a perceived need to keep on hiking rates in tandem with rate hikes in America, to ensure that SA bonds remain attractive to foreigners. Inflation in SA is certainly not caused by excessive demand and yet the SA Reserve Bank feels the need to keep on hiking rates regardless.

In the UK, inflation appears to be out of control, with second-round effects such as high wage demands accompanied by strikes becoming all too common. September inflation printed at 10.1%, up from 9.9% in August. The Bank of England is predicting it will peak at around 18% during the next year.

The usual suspects (high fuel and food prices) appear to be the main reasons for the rapid rise in inflation in Britain, but the collapsing pound is an even bigger factor. To put this in perspective, the price of a barrel of Brent crude oil was $97 just before the Russians invaded Ukraine but the £/$ rate was at 1.36 at that time. Today the oil price in USD is marginally lower but the £/$ rate is 1.13. This means that a barrel of oil in pound terms is now 18% higher than it was at the start of the war in Ukraine. Goods on the supermarket shelves are rising in price on an almost weekly basis, virtually regardless of where one shops. While the USD remains strong, thanks to rising US interest rates, the pound is likely to continue weakening, unless and until the Bank of England steps in and hikes rates meaningfully. Getting British inflation under control would be a difficult task at the best of times, but when also facing a political crisis, it becomes even more unmanageable. Jerome Powell and his members of the FOMC need to sit down and think very carefully about the consequences of their actions.

If they keep on hiking rates, hoping to get rid of inflation quickly and effectively, we may all suffer long-lasting economic damage.

Great insights.