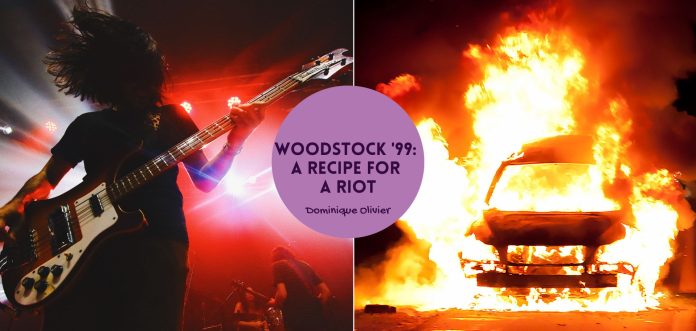

What do you get when you combine an unused airforce base, 220,000 teenagers, a couple of angry nu metal bands and some very expensive water? Part concert, part scene from an apocalyptic movie, the Woodstock festival that took place in 1999 was practically doomed from the start.

Ah, Woodstock – the 1969 festival that became an evergreen symbol of peace, love, and music. For three days, a muddy field in upstate New York became the center of the universe. Jimi Hendrix shredded a psychedelic version of the national anthem, Janis Joplin wailed her heart out, and The Who kept the music going well past sunrise. It wasn’t just a festival – it was a movement. A harmonious blend of music, free expression, and a collective yearning for societal change.

It was also a beautiful accident. The organisers were wildly unprepared for the sheer number of people who showed up (400,000 instead of the expected 200,000), food ran out, the weather was brutal, and yet (somehow) it worked. Against all odds, Woodstock became the ultimate counterculture moment, proving that a generation disillusioned by war, consumerism, and authority could come together, peacefully, in the name of music and something bigger than themselves.

It was a great thing. So, of course, they tried to recreate it.

Woodstock ’94 was the first attempt to recapture the magic. It had some solid moments – Green Day’s infamous mud fight with the crowd, Nine Inch Nails playing while covered in filth – but it also showed the cracks in the dream. A rainstorm turned the site into a swamp, security was overwhelmed, fences were trampled, and thousands of people got in for free. What was supposed to be a financially successful event ended up losing millions.

But even that didn’t stop organisers from trying once again.

The stage is set

Michael Lang, the mastermind behind the original Woodstock and its muddier 1994 sequel, decided to give it one more go for the festival’s 30th anniversary. This time, he teamed up with New Jersey concert promoter John Scher, hoping the third time would finally be the charm.

Sure, the 1994 edition had been a financial disaster, but the dream of pulling off a massive, profitable festival was just too tempting to resist. The chosen venue? Griffiss Air Force Base in Rome, New York – a decommissioned military site and Superfund cleanup zone. Sounds charming.

Determined to keep out gate-crashers, organisers erected a 3-metre-high plywood-and-steel “peace wall” and brought in 500 New York State Police troopers to guard it. Inside, the festival was an ambitious production featuring two main stages, a rave hangar, a sports park, and an Independent Film Channel-sponsored movie fest in a repurposed airplane hangar.

Even in the planning stages, it became clear very quickly that Woodstock ‘99 wasn’t about peace and love – it was about profits and logos. Corporate sponsors were everywhere, vendor “malls” sold overpriced essentials, and modern conveniences like ATMs and email stations reinforced the festival’s commercial edge. Ticket prices reflected the shift: $150 in advance (around $290 or R5,300 today) or $180 at the gate. They say you can’t put a price on making memories, but the organisers of Woodstock ‘99 sure gave it their best shot.

The descent into mud

As you’ve probably guessed by now, none of this ended well. In fact, there’s even a great Netflix documentary on what happened. With temperatures soaring past 38°C for the majority of the festival, the decommissioned Griffiss Air Force Base turned into a sweltering heat island. Vast stretches of concrete and tar soaked up the sun all day and radiated heat well into the night, leaving 220,000 festivalgoers with nowhere to escape. Shade was scarce, and with camping spots on the grass filling up almost immediately, many were left pitching their tents on the blistering tar.

The trek between the East and West stages was a grueling 3.7 km march across scorching pavement. And if the heat didn’t break festivalgoers spirits, the prices would. Thanks to aggressive cost-cutting, vendors were given free rein to set their own prices, leading to gouging that bordered on extortion. Bottled water was sold at $4 ($7.70 or R140 today). By Sunday, low stock levels and high demand meant that vendors were selling that same water for $12 ($23 or R420 today). Food supplies dwindled, and outside snacks had been confiscated at the gates, leaving many with no choice but to suffer through long lines or take a crowded bus to the nearest town’s stores, where shelves were quickly emptied.

The free water fountains seemed like a lifeline, but with massive queues and patience running thin, festivalgoers started breaking pipes to access water faster. This quickly resulted in mud pits forming all over the site. But these weren’t just any mud pits. Thanks to overflowing, under-maintained portable toilets, the water mixed with human waste, creating a literal cesspool of filth. Unaware (or just beyond caring), attendees jumped in to cool off, leading to outbreaks of trench mouth, trench foot, and general horror.

Trash cans were few and far between, and the ones that were there either overflowed or were repurposed as makeshift drums and rolling toys. Sanitation workers, overwhelmed or just unwilling to deal with the chaos, stopped showing up altogether, leaving the site to drown in its own filth. By the time the weekend was over, Woodstock ‘99 was less a music festival and more a dystopian survival experiment. And the worst was yet to come.

Break stuff

By Saturday night, Woodstock ‘99 had gone from plain gross to outright dangerous, with violence and destruction peaking during Limp Bizkit’s set. The crowd was already on edge, but when the band launched into Break Stuff, it was as if someone had flipped a switch. Mosh pits turned violent, plywood barriers were torn down and repurposed for crowd-surfing, and smaller buildings near the stage were ripped apart. At one point, massive chunks of plywood collapsed under the weight of concertgoers, sending people crashing onto others below.

Things only escalated from there. By Sunday night, as Red Hot Chili Peppers played Under the Bridge, a well-intentioned candlelight vigil for the Columbine shooting victims spiraled into something far darker. Some attendees used the candles to start fires, feeding the growing bonfires with whatever they could find – trash, plywood, even pieces of the supposedly indestructible perimeter “peace wall”. Flames quickly spread to both stages. When an audio tower caught fire, the fire department was called, but they refused to enter the festival grounds, fearing the increasingly hostile crowd. The tower eventually collapsed as people climbed its scaffolding.

Then came the festival’s grand finale: a laser show combined with Jimi Hendrix footage from Woodstock ‘69. But after days of suffering through brutal heat, overpriced essentials, and deteriorating conditions, the exhausted and furious crowd wasn’t exactly in the mood for nostalgia. The moment the show ended, mayhem erupted. ATMs were tipped over and looted, vendor booths were ransacked and torched, and trailers full of merchandise and food were broken into. In total, around $22,000 was stolen from the ATMs alone. Festival staff barricaded themselves inside control towers, while the few vendors still onsite abandoned their posts and ran.

By 23:45, law enforcement had finally had enough. Between 500 and 700 state troopers and local officers (many in riot gear) moved in, pushing the crowd away from the burning stages. Some rioters resisted, others scattered into the campground. The fires burned well into the morning before order was finally restored. What was meant to be a celebration of Woodstock’s legacy had ended in flames – both literally and figuratively.

Some things just can’t be monetised

If Woodstock ‘69 was about rejecting the system, Woodstock ‘99 was an illustration of what happens when the system runs the show. The original music festival in 1969 may have been chaotic, but it was real because it was built on a spirit of community and rebellion. Thirty years later, that spirit had been repackaged, sold off to the highest bidder, and drowned in sponsorship deals.

What was meant to be a tribute turned into a cautionary tale, proving that you can’t mass-produce a movement or cash in on a legacy without completely losing what made it legendary in the first place.

Editor’s note: Limp Bizkit is the one band that this ghost still hopes will come to South Africa – preferably without cancelling the tour this time. Also, in a context other than the chaos of Woodstock ’99!

About the author: Dominique Olivier

Dominique Olivier is the founder of human.writer, where she uses her love of storytelling and ideation to help brands solve problems.

She is a weekly columnist in Ghost Mail and collaborates with The Finance Ghost on Ghost Mail Weekender, a Sunday publication designed to help you be more interesting. She now also writes a regular column for Daily Maverick.

Dominique can be reached on LinkedIn here.